Originally posted on Kettering Foundation: https://kettering.org/africas-gen-z-democracys-last-line-of-defense/

The African continent has 400 million youths aged 15–35 years, and they are playing a major role in determining the pulse of democracy. Young people are the largest voting cohort in Africa. In South Africa, they constitute 42% of registered voters and are 62% of the voting population in Ghana. They have driven major protests, including the most recent one in Kenya. However, they have also supported coups in Niger, Burkina Faso, and Zimbabwe and have been at the center of popular uprisings that have yielded to military-led transitions in Egypt and Sudan. African youths prefer democracy to authoritarianism, but they are more likely than their elders to be dissatisfied with the way democracy is currently working in their countries. The danger is that if the aspirations of youth are not addressed via democratic processes, their dissatisfaction with the establishment may give way to support for authoritarian alternatives.

From Winds of Change to Autocratization

The coups pose a significant threat to the ongoing process of democratization that Africa earnestly began in the 1990s. During this time, the Wind of Change brought a legal shift from one-party states into constitutional multiparty democracies. A new compact against military coups was also formed. The African Union and the Economic Community of West African States adopted a resolution to not accept governments that emerged out of military-led establishments. The consensus lasted for at least a decade. Since the early 2000s, evidence is also pointing toward reversing these democratic transitions to non-democratic regimes in a third wave of autocratization.

Despite the role that young people have played in supporting recent military coups, there is excitement about the potential of a Gen Z-driven democratic consolidation across Africa. The Afrobarometer report also notes that late millennials and Generation Z have broadened their political behaviors beyond voting to embracing collective action to advance new democratic ideals. But the same youth have a greater willingness to tolerate military intervention when elected leaders abuse power. They are also less trustful of government institutions and leaders. Furthermore, the findings from the Afrobarometer survey may suggest youth attitudes toward democracy are contradictory, but they may also point toward flexibility in dealing with existing contexts. The youths are probably more interested in the performance of political regimes than the rhetoric of democracy. The Kenyan youth have been actively demonstrating against specific government policies. The public role of African youth has mostly entailed protesting (at times violently) against economic injustices, corruption, police brutality, governance, and election-related concerns.

- Since the Arab Spring, youth movements have helped remove long-term authoritarian regimes in Tunisia, Egypt, Sudan, and Zimbabwe. However, their role in Zimbabwe is somewhat disputed given the central role of the military in orchestrating the change of government.

- In Malawi, the youth played a central role in disputing what was perceived as a rigged outcome of the 2018 elections. The attention led to the nullification of the results and new elections.

- In Senegal, youths successfully protested former President Macky Sall’s decision to imprison opposition political leaders and postpone the elections. A number of youth leaders that had been arrested were then released, and the election postponement was ruled illegal.

- In Ghana, Nigeria, and South Africa, the youths have protested the unaffordable costs for tertiary education (#feesmustfall), police brutality (#endsarsnow), economic crisis, and rising youth unemployment. The abuse of international debt has been publicly rallied against in Ghana and Zambia.

These protests are not one-off events. In some countries—Ghana, Nigeria, Uganda, and South Africa—it has become normal to witness at least four protests a month. The specific grievance or rallying point may shift, but the root problems are always the economy, the increasing cost of living, and governance blunders.

In 2024, the Kenyan #RejectFinanceBill2024 protests have not only animated the African public space but also inspired movements beyond the continent. The Gen Zs of Kenya (a seemingly leaderless movement) successfully protested the imposition of a new tax that the government intended to use toward settling international debt. The original draft of the bill would have increased levies on basic daily needs such as fuel, mobile money transfers, internet banking, sanitary pads, and diapers.

These protests suggest a broadened understanding of democracy beyond elections. From the youths’ perspective, democratic governments should be able to resolve economic and social injustices. They are focused on reforming not only the national but also international political and economic frameworks. At the national level, they have sought to expose and, where possible, remove a corrupt and illegitimate government. At the international level, the Gen Zs have devoted their energies to challenging remnants of colonial power, especially in Francophone Africa and the international financial system. In Senegal, Burkina Faso, and Mali, there has been a consensus to challenge French hegemony in the affairs of former colonies. The youth vote in Senegal was in many ways an expression of their discontent with how the French continued to exercise power, especially around economic reforms and fiscal policy. Rallies in Kenya have been largely against President William Ruto, but protesters are also speaking out against the IMF. Gen Z protesters throughout the African continent are focused on the wasteful local elite and on what they call irresponsible lending and unfair interest rates.

Beyond Protests

Conversations about youth participation in the state of democracy across Africa are often reduced to a counting of first-time voters. Such discussions remain disconnected from the wide-ranging protests discussed above. The protests are usually successful. In Kenya, after six weeks of demonstrations and a promise to reverse the bill, President William Ruto fired his cabinet and pledged to cut wasteful spending.

However, there is limited evidence to suggest that youth-led movements have imagined new democratic frameworks beyond their participation in voting, protesting, and ensuring accountability. Youth-led organizations focused on government accountability have grown in number and influence over the years. They have leveraged technology to track government expenditures, established commitments to policy reform, and mobilized more youth participation. They have pushed back on the global financial system and its treatment of poorer countries. However, all these actions can appear to be simply tinkering on the edges of a continent that may be drifting into a new era led by popular authoritarians. To avoid this outcome, the youth movement must continue to play a more active role in governance instead of simply being facilitators of political transitions.

An overview of my blogging journey in 2024

I have used the blog form of writing for a while now to share insights from my research with a broader audience. In 2024 I published twelve blog posts covering various themes, including democracy, development, agrarian reforms, and personal development. While the responses have varied, my letter entitled "Dear Dalitso" has garnered the most interest. In this overview, I have taken the opportunity to reflect on my blogging journey month by month and to compile all the links to each blog in one convenient location for the reader's ease of access.

In February, I published a blog titled “ The Big Bet”. 2024,” which sparked significant discussion among colleagues. The blog has reached 133 views, while the accompanying podcast has garnered 223 views. It critiques the diminishing emphasis on community assets in development discourse, which is often overshadowed by state behaviour. The central argument is that engaged citizens, and local associations are vital for fostering democracy and inclusive development. In this blog I argue against reducing democracy to mere electoral events, emphasizing that true democracy involves public problem-solving across society. Observations from Zimbabwe, Malawi, and Zambia reveal that government performance frequently falls short of citizens' needs, perpetuating poverty, and inequality. However, communities show resilience through both informal and formal networks of solidarity, essential for resource pooling and addressing local challenges. The blog advocates for a renewed focus on community associational life, highlighting grassroots efforts to enhance accountability and improve livelihoods.

I then worked on a series of writings titled the "Democracy and … Series during which I explored various aspects of democracy, all of which were composed from March 7th to March 10th. The inaugural publication in this six-part series highlights a pressing global consensus, how democracy is in decline while authoritarian regimes are gaining strength and solidarity. This troubling trend is underscored by the 2020 Democracy Index from the Economist Intelligence Unit, which revealed that only 49.4% of the world's population lives under some form of democracy, with only 8.4% in "full democracies." The series calls for critical reflection on this decline, particularly in Africa, where military coups, one-party rule, and authoritarianism prevail. It points to public dissatisfaction driven by corruption and ineffective governance, arguing that mere elections are not enough. Genuine democracy requires enhancing public freedoms, citizen engagement, and equitable resource distribution. The series seeks to explore ways to revive democratic ideals, emphasizing democracy as a continuous societal commitment rather than just an electoral event.

Let’s Talk About Democracy: A Definitional Crisis dives into the pressing concerns surrounding the perceived threats to democracy in an era marked by rising authoritarianism globally. I highlight significant challenges to established political and governance frameworks, including events like the attempted coup in the United States, the rise of right-wing nationalism, and a resurgence of military coups, alongside China's growing influence. I argue that these issues may signal a crisis in how power is exercised, often benefiting a select few. It outlines three democratic frameworks—consensus, constitutional, and deliberative democracy—highlighting the importance of citizen engagement. Despite the threats, grassroots movements and global citizen initiatives offer hope for revitalizing democratic practices. I make a call for a reimagining of electoral systems to reflect the will of all citizens, promoting a more inclusive and equitable democratic future.

In my blog, “Democracy and…The Principle of Adequate Representation” I dive into the evolution and challenges of democracy, tracing its origins to Ancient Greece, particularly the reforms of Cleisthenes, who established citizenship as the basis for political responsibility rather than clan affiliation. Although this shift enabled broader participation, it also led to early exclusionary practices based on wealth and education. I argue that despite democracy's connection to the French Revolution and universal suffrage, achieving meaningful representation remains difficult due to social cleavages such as race, language, and gender. Focusing on Zimbabwe, I critique local representation hampered by tribalism and the disconnect between leaders and constituents. I advocate for an inclusive approach that genuinely reflects the interests of marginalized groups like women and youth, urging political parties to go beyond superficial practices. Ultimately, the blog underscores the necessity for a participatory democracy that addresses community-specific challenges through evidence-based policy-making and grassroots engagement.

In my fourth piece, "Democracy and the Principle of Effective Participation " I highlight the importance of citizen participation in democracy. I argue that effective governance relies on amplifying local voices, upholding the rule of law, and fostering equity. I define citizenship as active engagement in governance rather than mere legal status. Despite Zimbabwe's constitutional mandate for inclusive participation, I pointed out numerous challenges citizens face in engaging with their government. While mechanisms like public protests and local consultations exist, genuine participation often feels elusive due to perceived powerlessness and superficial frameworks. For further exploration, I discussed these themes on the podcast “What If - What If There Is an Alternative: Is Participation the Missing Key?” which received 173 views, highlighting its relevance.

"Democracy and the Principle of Cooperation," addresses critical issues surrounding the evolution of political systems and the role of civic engagement in democracy, particularly in the context of Zimbabwe. I critique the traditional view of democracy as merely a function of voting, emphasizing that true democratic engagement requires active citizen participation beyond electoral processes. Drawing on historical perspectives from thinkers like Thomas Hobbes and Alexis de Tocqueville, I argue that democracy is inherently a social construct that thrives on cooperation and collective action among citizens. I also highlight the importance of civic agency, which can be cultivated through grassroots associations that reflect the unique needs and challenges of communities. These associations not only foster political participation but also serve as incubators for democratic values and practices. Furthermore, I underscore the necessity of a 'with' approach, i.e. government working with citizens to enhance mutual efforts between state and society. I then call for greater recognition of local associative forms as vital components in deepening democracy, suggesting that these grassroots movements can significantly contribute to national discourse on governance and civic responsibility.

In the sixth instalment of the “Democracy and…” series, titled "Democracy and the Principle of Economic Inclusion: Part One," I delve into the critical intersection of democratic governance and economic inclusion. I address the decline of democratic values during economic crises, citing a 15-year trend of democratic recession, particularly in Africa, where coups, intolerance, and human rights violations are rising. I also argue that many public protests are driven by economic grievances rather than demands for democracy. While acknowledging progress in African democratic frameworks, I identified persistent economic weaknesses that hinder true democratic development. I also criticized free-market models for increasing job losses and inequality, widening the gap between elites and the majority. Advocating for a reassessment of economic strategies, I call for integrated value chains, innovative funding for industrialization, and greater citizen engagement in reform efforts, moving away from reliance on political and business elites. I then concluded by stressing the urgent need for an inclusive economic framework to support democratic values and tackle issues like unemployment and inflation.

On July 20, 2024, I published a blog titled "AfricaGiving-More Than Just an App!" that examines the work of our innovative AfricaGiving app, which my organisation, SIVIO Institute launched in 2023, on the African philanthropy landscape. This innovative platform seeks to address the challenges local non-profits face in securing sustainable funding and visibility while emphasizing the need for a change in basic assumptions in philanthropy. It facilitates direct giving across diverse contexts, strengthens organizational governance, and fosters trust through rigorous vetting processes. I note the importance of building relationships between individual donors and organizations, advocating for a cultural shift towards online giving. The blog also highlights the successful "100 for $100" campaign, showcasing the app's capacity to connect donors with meaningful causes and promote collaborative philanthropy. Overall, AfricaGiving is positioned as a crucial tool for enhancing community-driven initiatives and nurturing a culture of giving in Africa.

On July 23, 2024, I published a blog titled "South Africa’s Elections Are a Warning Sign for Democracy," featured on the Kettering Foundation website. This analysis, following the May 2024 national elections, examines the African National Congress's (ANC) decline, as it secured only 40.2% of the vote—the lowest since 1994. I highlight voter disillusionment due to the ANC's unfulfilled promises and internal divisions that led to breakaway parties capturing 24.1% of the vote. I caution that without a renewed focus on inclusive economic development and effective governance, South Africa's democracy is at risk. The blog emphasizes the urgent need for the ANC to tackle governance issues, corruption, and rising inequality to preserve stability and democratic integrity.

Fifteen days after Rwanda's elections (30 July 2024), Nyasha McBride Mpani and I published an article titled "Freedom of Choice in Rwanda’s Presidential Elections is an Illusion," in Mail & Guardian. The analysis critiques the political situation following President Paul Kagame's 99% vote win, questioning the legitimacy of such results amidst his long-standing presidency since 2000 and the lack of viable alternatives for voters. We contextualize Kagame's popularity within Rwanda's post-genocide recovery, comparing it to the ongoing struggles in countries like Zimbabwe. We express concerns about political dissent suppression, exemplified by the imprisonment of opposition figures like Diane Rwigara, complicating the electoral transparency debates. Ultimately, we argue that despite Kagame's contributions to stability and development, Rwanda still lacks genuine public participation and political pluralism, challenging the nation's quest for effective governance alongside democratic freedoms.

In the article "Latest Developments on Land Tenure Reforms in Zimbabwe," published on October 10th, 2024, I examine the Government of Zimbabwe's announcement on land tenure changes for fast-track farms, which introduces bankable titles allowing landowners to borrow against, sell, or subdivide their property, with restrictions on sales to 'indigenous' citizens. The blog discusses the potential benefits, such as improved financing, enhanced agricultural productivity, and a new land market, while also addressing challenges like land concentration and the need for effective governance to tackle issues with land barons. My dedication to land and agrarian issues is evident in my previous works, which serve as valuable resources for enthusiasts seeking to explore these topics further. These include the policy brief "To Compensate or Not To? Revisiting the Debate on Compensation for Former Large–Scale Farmers in Zimbabwe," the policy insight "titled The Past in the Present: Challenges of Protecting Customary Tenure Provisions - The Chilonga Case," and the article "titled Exploring The Tenure- Nexus on Customary Land Right Holders ." Additionally, I explored the impact of land reform on agricultural practices in Zimbabwe through the What If Podcast,where I examined the impact of land reform on Zimbabwean agricultural practices nearly 25 years post-fast-track implementation, discussing the necessity of these reforms and potential future pathways for the sector, which has garnered 126 views and is available on Spotify and Apple Podcasts. The discussion emphasizes the necessity of these reforms and future directions for the sector.

On December 24, 2024, I concluded the year with a blog titled "2024: The Year Democracy Was Tested in Africa," originally featured in Mail & Guardian. In this analysis, I distill the critical issues surrounding democratic governance across the continent, highlighting the significant costs of conducting elections in Africa, averaging $4.20 per capita—double the global average. Increasing public scepticism towards electoral commissions, coupled with a demand for accountability, underscores the electorate's impatience for substantive change rather than mere power shifts among elites. The blog also discusses the ideological evolution in African politics, with a shift from personality-driven politics to performance-based assessments of governance. While there are signs of deepening democratic practices, a concurrent rise in authoritarianism poses a threat to progress. I argue that elections alone are insufficient for true democracy, emphasizing the necessity of broad citizen engagement and governance focused on development rather than perpetual electoral cycles.

These are just my views based on various readings and field research. The only conclusion I make is that democracy is a work in progress. It is not necessarily about elections but more about citizens engaged in fixing public problems collectively. The year ahead is going to require even more work from all of us. At times, we restrict ourselves to focusing only on who to vote for; that is important, but we need to go beyond that. How else can we contribute towards the change that we desire?

For more information on my writings, visit

As we step into 2025, there is a palpable sense of anticipation for a brighter future across various facets of our lives, including the state of our democracies. The past year has been a mixed bag for African nations, with several countries undergoing elections that yielded new political dispensations including new administrations led by former opposition parties and in some instances governments of national unity. In some cases, the incumbent parties retained power. It was a year in which electoral democracy was tested (Mail & Guardian). The consensus around electoral democracy has been somewhat restored.

What then should we look out for in 2025?

The previous rounds of elections have demonstrated that changing leaders or political parties although necessary is not enough. Elections are a crucial component of democracy; they are not sufficient on their own to ensure transformative development. The reality is that many African electoral democracies have not delivered the expected outcomes, often resembling undemocratic regimes where elites prioritise personal gain over public service. We hold on to the statement that elections are a necessary but not sufficient condition for democracy. Perhaps the biggest disappointment for the electorate is to see those in new administrations behaving the same (if not worse) as the previous regime that they would have voted out. This happens across many countries on the continent.

What then is the missing part of the puzzle?

In our earlier writings, we have made a case for citizen-centred democracies. In this big bet, we build upon an ideal of citizen-centred democracy. One of the most pressing issues highlighted in recent discussions is the need for accountability in our democratic systems. The lack of accountability on the part of public officials has led to stagnation in Africa’s development agenda, and we must do more to hold our leaders accountable

It involves holding governments to a standard of performance and ensuring that they face consequences for bad governance, abuse of public resources and ineffectiveness. However, the current political landscape often complicates this process. Legislative bodies, which are supposed to oversee government actions, frequently operate under the same political party affiliations as the executive branch, creating a conflict of interest that undermines accountability. This has resulted in widespread allegations of corruption and abuse of power, further eroding public trust in government institutions. To address these challenges, there is an urgent need for citizens to expand their repertoire of public work beyond just casting their votes.

The concept of accountability is fundamental to a functioning democracy.

In 2025 we are making a bet on citizens to build upon their collective energy to come together in various associational and institutional platforms, demanding accountability from public officials at both national and local levels. If anything, the agitations amongst Gen Zs in Kenya, Senegal, Ghana and Nigeria provide hope for a citizen-driven redefining of democracy and good governance.

The big bet is that a consensus around accountability will significantly improve the quality of our democracies across Africa. In many instances, the assumptions have always been that Africa’s leaders will be moved by a certain moral compass towards duty, integrity and effective delivery of mandate. There is reason to believe that either the moral compass has been lost or sacrificed at the altar of personal accumulation.

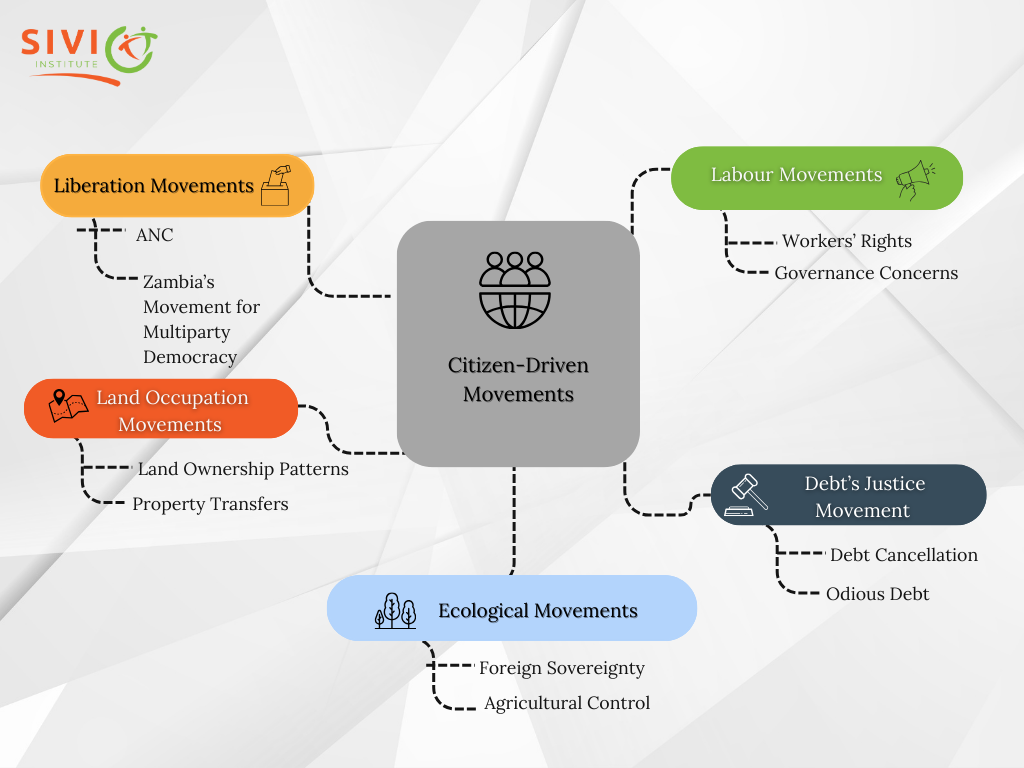

Figure: History of Citizen-Driven Movements of Accountability

Several civil society organisations have already begun to pave the way for accountability-focused initiatives. For instance, platforms like Corruption Watch and BudgIT Nigeria have worked tirelessly to expose corruption and track government performance. These efforts are crucial, but they must be expanded and integrated into broader social movements to create lasting change. Currently, many citizen-led initiatives emerge in response to crises, often achieving short-term gains but lacking the mechanisms for sustained impact. By collaborating with established civil society organisations, these movements can enhance their effectiveness and ensure that accountability remains a central theme in the political discourse. Moreover, tracking the conversion of electoral promises into actionable policies is essential. Political parties often present lengthy manifestos filled with promises during election campaigns, yet these commitments frequently go unfulfilled. Citizens must demand action from their leaders on promises and pledges and ensure that they translate into tangible actions that benefit the public.

As we look ahead, it is crucial to foster a culture of accountability that permeates all levels and sectors of governance, including health, education, and public finance. This requires a proactive approach, where citizens are not just passive observers but active participants in demanding transparency and good governance. The role of the media, civil society, and grassroots movements cannot be overstated in this endeavour. In conclusion, the journey towards a more accountable and effective democracy in Africa is a collective responsibility. As we enter 2025, let us commit to revitalising our democratic processes by holding our leaders accountable and ensuring that they deliver on their promises. By doing so, we can create a brighter future for all citizens, where democracy truly works as it should.

The time for action is now, and together, we can make a significant impact on the trajectory of our nations.

There is a new consensus, democracy is on the decline and authoritarian regimes are consolidating, expanding and exercising solidarity with each other. Could this be the moment for a post-democracy compact or the reinvention of democracy? A lot has already been written about this subject- see for instance the Pew centre report on dissatisfaction with democracy here . According to the Democracy Index published by the Economist Intelligence Unit, the 2020 global average score for democracy fell to its lowest level since the index began in 2006. The same report cited above provides a snapshot of global patterns as follows.

…only about half (49.4%) of the world’s population live in a democracy of some sort, and even fewer (8.4%) reside in a “full democracy”; this level is up from 5.7% in 2019, as several Asian countries have been upgraded. More than one-third of the world’s population live under authoritarian rule, with a large share being in China.

In the 2020 Democracy Index, 75 of the 167 countries and territories covered by the model, or 44.9% of the total, are considered to be democracies. The number of “full democracies” increased to 23 in 2020, up from 22 in 2019. The number of “flawed democracies” fell by two, to 52. Of the remaining 92 countries in the index, 57 are “authoritarian regimes”, up from 54 in 2019, and 35 are classified as “hybrid regimes”, down from 37 in 2019.

However, many writings including the reports cited above do not adequately interrogate how we got here. There is a need for an urgent and a somber reflection in order to move forward. There is an ongoing project of examining present day challenges of democracy across the world, see for instance the work of Freedom House, Kettering Foundation, and many others. The overall concern in most of these platforms is based on the real decline in the number of countries that fit the tag of being called a ‘democracy’. In Africa, the concerns around the collapse of democracy are manifest in at least three ways- the return to military led coups, the entrenchment of one-party rule through manipulations or mutilations to the constitution and subtle authoritarian creep using state resources to buy off the opposition.

There is an increasing number of surveys where respondents have confirmed their dislike for the current status quo around democracy due to corruption amongst the elites and failure of the state to equitably redistribute resources. According to the PEW Centre[1] most of the respondents from 27 countries believe that elections bring little change, that politicians are corrupt and out of touch and that courts do not treat people fairly. There are many explanations behind the decade long of processes of undoing the march towards democracy.

In Africa the Economist magazine notes the return of military coups as problematic and parks the problem at incumbent regimes, most of which claim to be democratic. These have brought neither prosperity nor security. Real GDP per person in sub-Saharan Africa was lower last year than it had been ten years earlier. The Economists proceeds to argue that more people are dying in small conflicts than at any point since at least 1989. In Nigeria, schools have been abducted. When people lose hope that their lives will improve, they become impatient for change and the risk of coups and civil wars increases sharply.

Maybe the spectacular return of coups has not been adequately understood. There are two sides (nothing new right). What is apparent to all of us is that civilian governments subjected to coups will have failed their citizens somewhat. In this instance these coups are a response to leaders who have personalized government and violated the constitution and made it seem impossible to remove them from office. The coups in this instance are seen as a popular response to authoritarianism. However, the post-coup arrangements do not necessarily point towards the deepening of democracy. In countries such Niger and Burkina the post-coup regimes have reversed trade relations with France especially around natural resources. It is reported for instance that the coup in Niger may have a positive influence on economic development based on new terms of exploiting natural resources.

However, others such as Brian Kagoro, [2]Everisto Benyera and Sabelo Gatsheni, make the connection between the coups of the 1970s into the 1980s with those happening in present day Africa. They argue that the cessation of coups in the later 1990s into the 2000s was not necessarily due to improved conditions of democracy but rather the period coincided with the peak of the unipolar world- dominated by the United States. In this regard the contestations for spheres/territories of influence had dissipated. The resurgence suggests a renewed and frenetic for territorial influence and natural resources. However, it is also true that these coups are not being manufactured and led by foreign intelligence services like in the past.

Another point to be made about this moment is the fact that Africa as a continent has all along been engaged in what has been referred to by others as ‘isophormic mimicry’. This has been explained as a technique in which governments create the outward appearance of highly functioning development institutions to conceal their dysfunction. It has at times been limited to development but there is a growing realization that the institutions to support/enhance democracy face similar challenges. Institutions such as the courts and elections commissions either do not have necessary autonomy or sufficient capacity to enhance democracy. Most of the so-called democracies in Africa are cheap imitations. The main challenge has to do with limited constraints on the Executive branch of government. Usually, an effective judicial system and a strong civil society provide balance to powerful executive branches. But these have been severely eroded over the years. In many African countries, though, rulers allow the opposition to participate in elections but take a thousand precautions to ensure they cannot win, from tampering with the voters’ roll to throttling the media. No fewer than nine African leaders have been in power for more than 20 years. It is hard to expect people to support democracy if all they have experienced is a masquerade of it. In some instances, the preferred term is backsliding of democracy. The causes are usually the same, increasing inequality, an insensitive political elite, populist politics without delivery of public goods and collapse of the development project.

There is an urgent need for conversations and broader mobilization to reset the movement towards inclusive democracy. As noted, the version of democracy that was brought into Africa has been inadequate. Perhaps its biggest weakness is the failure to create a strong connection with the economy beyond the assumptions of market led laissez- faire type of growth, it remains captured by the dominant elite and is subject to manipulation. Furthermore, it has, without intent, led to demobilization of citizens- in many instances the achievement of universal suffrage was viewed as the sine qua none of democracy-yet it should have been as only the beginning. What must we do? In this ten-part blog series I explore ways towards recovery of the democracy project. The main argument is that legislating for multi-party politics and holding regular elections is not enough but probably just the first step. Democracy is a way of public life and not an event. Measuring whether an election is free and fair whilst necessary it also not an adequate measure of democracy. It is a measure of elections. The two are not synonymous. How then do we measure democracy? I make the proposal to apply three related measures to determine the extent to which a country is democratic; (i) the freedoms in the public space (AGORA), (ii) the intensity of citizen-to-citizen engagement in solving public problems and finally the extent to which elections are judged to be free and fair.

Bibliography

- Democracy index 2020 - Economist Intelligence Unit. (n.d.). https://pages.eiu.com/rs/753-RIQ-438/images/democracy-index-2020.pdf

- Wike, R. (2019, April 29). Many across the globe are dissatisfied with how democracy is working. Pew Research Center’s Global Attitudes Project. (https://shorturl.at/cfvC1)

- (2023, May 20). Africa is not broke, Africa is broken | Brian Kagoro. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ifaP5sEVFlA

[1] https://shorturl.at/awC04

[2] Africa Is Not Broke, Africa Is Broken | Brian Kagoro - YouTube

There is talk among many that democracy is under threat, and we are in a period of increasing authoritarianism around the globe. There is widespread evidence of the challenges confronting the prevailing and widely accepted political and governance mechanisms. These include but are not limited to, the attempted coup in the US, increasing intolerance, right-wing nationalism, resurgence of military (popular) coups, and the rise of China. These point towards a major problem in how power is exercised at times for the benefit of a few.

Are these problems pointing towards the collapse of democracy? Our challenge is perhaps we lack conceptual clarity on what we mean by democracy. At the core of democracy is a culture of civility, tolerance, and a commitment to the public space. Over time, however, we have adopted a narrow definition of democracy where it is reduced to the holding of regular elections to decide the new band of officeholders. That is almost like the definition of a republic but not necessarily democracy. Based on this popular but narrow definition we have devoted significant attention to how we hold elections. These are important considerations in any democracy. They ensure that citizens are satisfied and feel that they are represented by the people they choose. Thus, we always argue that ‘elections’ are a necessary but not sufficient condition for democracy. One may ask- what then is outstanding in this equation? Some of us would argue that engaged citizens and the public work that they do are the vital lifeblood of a democracy.

Whilst here let me state that there are three other ways of looking at democracy viz (i) consensus democracy – rule based on consensus rather than traditional majority rule. (ii) Constitutional democracy – governed by a constitution. (iii)Deliberative democracy – in which authentic deliberation, not only voting, is central to legitimate decision-making. In many instances when we talk of democracy, we are referring to constitutional democracy.

In all instances/frameworks of democracy, citizens should be expected to occupy centre stage, again not in that narrow way of delineating who belongs to a country but rather as a distinction with officeholders. Democracy can and should be seen as a centuries-old people’s movement looking at how we can govern ourselves after throwing away the shackles of the monarchy (a symbol of oppression in a particular age). In that regard, democracy is about influencing forms of social organization and collective action to resolve public problems away from what was the preserve of the feudal structures of power. The American and French revolutions played an important role in ushering the democracy under discussion. Tocqueville’s treatise: Democracy in America’ delves deeper into the emerging forms of social organization- especially voluntary associations in that period. This may not look revolutionary today, but it was a novel way of re-organizing society outside of the monarchical feudal relations that existed.

The above definitional argument allows me to proceed to the central argument in this discussion- not all of democracy is under threat but certain aspects of it. The democracy with a small ‘d’ project - the undertakings of citizens (national and transnational) amongst themselves is probably at its peak. Globalisation was initially promoted as an economic project of interdependence. Equally so there is a newly discovered consensus on the need to jointly solve wicked problems. The wicked problems around climate change, the global economic crises, inequality, and poverty are best articulated and resolved in citizen-to-citizen platforms- commonly organized in what we loosely refer to as civil society organizations. Despite concerns to do with unresolved but stark unequal power relations- the global citizen-to-citizen platforms offer us the best possibilities for re-imagining and understanding the strides we have made to sustain democracy. In these spaces we practice (albeit unevenly) values of civil society and mutual respect, we talk about social justice, and accountability, we frown on racism and historical injustices. It is these global mobilizations of ordinary people from various walks of life that should give us hope. These mobilizations have gone through various ebbs and flows- perhaps they were at their peak during the various World Social Forums. People-to-people solidarity. Our democracy is deliberative.

The democracy project with a capital ‘D’ referring to the allocation of power and resources within a country is under threat. At the centre of the threat is the system of free and fair elections requires urgent attention and rethinking. In many instances, these elections produce cliffhanger results and still, the winner must take all with no adequate consideration of the significant minority that didn’t vote for the victorious party or individuals. Take for instance the Democratic Party in the US- they have always won the majority vote in the US since the 1980s and yet they have not necessarily won the right to run the White House due to a very complex process called the electoral college. These challenges are not unique to the US. In many African countries, the ruling political party takes advantage of its incumbency to have a final say over constitutional boundaries. The resolution of the democracy with a capital ‘D’ is within reach thanks largely to the strides that citizens have achieved in establishing various initiatives from the local, national, regional, and global processes. It is these processes that will help shape and define the next phase of the struggle for democracy with a capital ‘D’. There is hope.

In its original formulation democracy was always about direct representation. It originated in the City of Athens (Ancient Greece)- and Cleisthenes also spelled Clisthenes, (born c. 570 BCE—died c. 508) is credited as the founder of modern-day democracy. He successfully allied himself with the popular Assembly against the nobles (508) and imposed democratic reform. Perhaps his most important innovation was the basing of individual political responsibility on the citizenship of a place rather than on membership in a clan. The shift was significant. It led to the thinking of citizens as actors in the public and allowed for the expansion of settlements beyond clan-based systems.

However, even then there were already signs of excluding others. Many philosophers devoted time and thought on what kind of citizen should be part of the public space (the Agora). There were new nuances around wealth and levels of education. Growing populations made it necessary to consider a framework of representation. During the period preceding the industrial age (feudal era), those who did not hold land (known as serfs or peasants) had no public representation. They were subjects of their feudal lords. The lords had ways of representation and engaging with the monarchy, but it was hardly a democracy. For many, modern-day democracy derives its roots from the French Revolution of 1789. The revolution was inspired by ideas of equality of egalitarianism and led to the overthrow of the monarchy in France and in many other places. In its place emerged a new consensus around representative democracy.

Since then, battles have been fought across the globe on the need for universal suffrage. The right to vote for one’s chosen representation. Universal suffrage has been achieved in many parts of the world, but effective representation has not yet been achieved. There are old and new cleavages in society that had either been previously ignored or have recently emerged. However, not all democracies are the same. The achievement of universal suffrage is not an end but may be a great starting point for ensuring adequate representation. One of the assumptions of representation is the idea of voice- the representatives have a voice to speak on behalf of their communities. But as many others have shown not all democracies are the same, according to the Varieties of Democracy project there are four categories of regimes; (i) closed autocracy, (ii) electoral autocracy, (iii)electoral democracy, and (iv) liberal democracy (https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/political-regime?time=2022). These varieties of democracy also point towards uneven levels of representation.

One of the conditions for democracy to work is the need to make sure there is adequate representation in local and central government processes. Differences in society usually manifest through racial, language, demographic, and gender-based groups. In some instances, geography matters. Take for instance the ongoing public fight within Zimbabwe’s largest opposition party around recalls. It seems one of the major complaints amongst those doing the recalling of Members of Parliament is the challenge they face in being represented by people who do not originate from the same area and are also not of the same language group. In a polarized environment, these concerns have been reduced to ‘tribalism.’ At the centre of democracy is the idea that everyone’s voice must be heard. The responsibility and processes of choosing a representative cannot be subcontracted to a party’s leadership. The communities must feel that they have a stake in the process and should have confidence in the process. Anything lesser than this golden standard will lead to alienation from the public space and frustration.

The achievement of adequate representation also requires consideration of groups that have been historically excluded from holding public office. The historically excluded include women, youth, language/tribal minorities, and special interest groups (such as people living with disability). Several African governments have come up with quota systems for public offices to ensure improved participation of women, youths, and in some instances, people living with disabilities. Several constitutions written in the 1990s and 2000s have made significant progress in ensuring that there is adequate representation.

However, there are ongoing concerns that some governments have been undoing some of these provisions. Perhaps the real challenge has nothing to do with legislation, but the focus must instead shift towards practices within political parties vying for office. How have these entities established norms and frameworks to enhance adequate representation within political party processes and in the selection of their leaders? Political parties, just like governments face the real risk of isomorphic mimicry- where they may seem (to outsiders) as democratic when in fact there is a single leader or a cabal of established elites making all the decisions. There is a need for a thorough examination of the different social and demographic groups/interests within the party and the extent to which they are represented. Diversity is beautiful but it can lead to fragmentation if the different groups are not adequately represented. Adequate representation not only in terms of holding office but in the day-to-day decision-making processes should the North Star of a political party pursuing public office. Otherwise, what is the guarantee that they will be democracy after winning the elections?

There is another dimension to representation- the need to make sure all public problems/ issues are given adequate consideration. Communities are not the same-they face different and at times unique challenges. There is always an assumption that representation by area resolves challenges to do with uneven development. In many instances, representatives can be marginalized especially in the absence of an evidence-driven policy-making culture. Representation requires effective bottom-up participation (see next post)

Democracy depends on increasing the voice of local communities, respecting the rule of law, promoting equity and justice, and the participation of the beneficiary communities in decision-making. Broad participation has been identified as a potential antidote to the unfettered expansion of expert-based approaches that exclude citizens. Effective participation depends on the recognition and affirmation of the right to engage. In many instances, we loosely refer to those who are able or aspire to effectively participate in public problems as citizens. For this blog series, I consider a citizen as one who shares in governing and being governed in the best state, he/she is the best able one and chooses to be governed and govern with a view to the life of excellence (adapted from Everson 1988- see also Murisa, 2020). Traditionally citizenship has been viewed as relating to belonging to a state and enjoying its rights while simultaneously fulfilling obligations required by that state (Turner,1997; Masunungure and Koga, 2013). In this discussion, I focus on citizenship as a verb entailing the actions taken by citizens individually and collectively to improve the public space. Citizenship is the bedrock against which individuals can claim services from their government or seek to participate in national processes, including for or being voted into office (Masunungure and Koga, 2013).

The Zimbabwean Constitution affirms broad-based participation in national processes as an indivisible right. Section 13 (2) of the constitution obligates the Government to

"…involve the people in the formulation and implementation of development plans and programs that affect them". Citizens acknowledge the need for their engagement with officeholders but indicate facing multi-layered challenges in seeking that engagement (International Republican Institute 2015, Ndoma and Kokera, 2016).

As individuals become more acquainted with the democratic process they gain more confidence, which makes them more effective advocates for reforms to specific policies.

Typically, citizens participate in the public space in different ways, including engaging in forms of solidarity towards one another, protesting unjust/unfair decisions, coproduction with formal organizations, and political decision-making (voting). The most common or popular forms of civic participation have been through public protests (see Murisa, 2022: 94-109). Yet there are several instances of other effective citizen-led/inspired participation. Zimbabwe has normative frameworks for citizen participation for the individual to influence practices and policies both at local and central government levels. These include budget consultations, participating in local government elections, being a part of consultative forums, public hearings, councils' open meetings, the Village Development Committee (VIDCO), Ward Development Committee, Rural District Development Committee, and Provincial Development Committee (Chikerema, 2013:88-89).

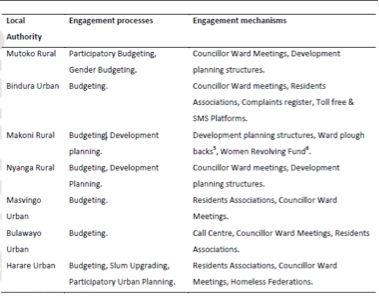

Figure 2: Citizen engagement processes and mechanisms Source: Muchadenyika, 2017

However, effective citizenship or participation does not happen by itself. Citizens may feel powerless or do not see the need to exercise control of their communities and national future. Furthermore, effective citizenship may be constrained when officeholders within government and formal non-state organizations create the 'impression' of participation when the end goal has already been established. Several formalized organizations working within the civil society space have carved a niche as an alternative to an ineffective and corrupt state and a rapacious business sector and have positioned themselves as the unelected and un-legitimized voice of the citizens. They have not necessarily invested in developing the voices of the poor and bonds of trust that can be used to unleash community participation in local and national processes outside of the framework of the scope of a defined project. Participation of citizens is an ideal that many official processes have failed to achieve and instead, they have created 'invited' spaces which in effect serve to constrain rather than unleash the civic capacities of citizens. Participation theorists such as Cornwall (2008), Gaventa (1993, 2005), and Chambers (1983) have contributed important insights to the dilemmas of effective participation. Eversole (2010:37) captures this dilemma in a very precise way when she observes that:

…the problem of participation is not that participation is impossible to achieve; but rather, that it is impossible to achieve for others… Rather, the challenge of participation is about how to become participants in our rights: choosing to move across institutional and knowledge terrains to create new spaces for communities and organizations to 'participate' together.

Many existing initiatives of participation are characterised by 'invited' spaces and managed projects instead of what Cornwall (2008) terms spaces that people create for themselves. Gaventa (2005) weighs in by suggesting that for there to be effective participation there is a need to work on participation from both sides of the equation: that is, to increase both the participation of communities and the responsiveness of government institutions. The challenge for Zimbabwe and indeed other emerging democracies is to remake participation through the reframing of interactions amongst communities, professionals, and institutions into a truly participatory space. A supply of good institutions and organizations is not enough. To create them by legislative edict does not make them work. Somehow people must be empowered to insist on good governance according to their terms. But wanting it does not make it happen. Institutions will work when a public covenant builds around them and demands that they work. A civic compact between formally established organizations and communities is what makes it sustainable, and it should begin at the level of communities. Only then can it be usefully facilitated by the well-placed civic investments of philanthropic donors. Civic values must emerge organically from the public life of communities.

Bibliography:

Aristotle. (trans. 1932). Politics (H. Rackham, Trans.). Harvard University Press

Chambers, R. (1983). Rural development: Putting the last first. Longman.

Chikerema, A. F. (2013). Citizen participation and local democracy in Zimbabwean local government system. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 3(11), 88-99.

Cornwall, A. (2008). Unpacking 'participation': models, meanings, and practices. Community Development Journal, 43(3), 269-2831

Gaventa, J. (1993). The powerful, the powerless, and the experts: Knowledge struggles in an information age. In P. Park, M. Brydon-Miller, B. Hall, & T. Jackson (Eds.), Voices of change: Participatory research in the United States and Canada (pp. 21-40). Bergin & Garvey.

Muchadenyika, D. (2017). Citizen engagement processes and mechanisms. In R. M. Chakaipa & S. Mudimu (Eds.), Local government reform in Zimbabwe: A policy dialogue (pp. 133-152). African Books Collective

Murisa, T. (2020) Whose Development: Examining the Extent to Which Development Actors Align with Communities.

Murisa, T. (2022). Rethinking Citizens and Democracy. SIVIO Publishing. Harare.

Ndoma, J., & Kokera, H. (2016). The role of the international observer in the consolidation of democracy in Nigeria: A case of 2015 general elections. European Journal of Political Science Studies, 4(3), 34-80. Retrieved from EJPS website.

Turner, B. S., Masunungure, E. V., & Koga, H. (2013). Citizenship in Africa: The politics of belonging. Africa Development, 38(3), 1-18.-18.

Political systems have evolved over time. Thomas Hobbes (1651) argued that within each of us lies a representation of general humanity and that all acts are ultimately self-serving. He suggested that in a state of nature, humans would behave entirely selfishly. He concludes that humanity's natural condition is a state of perpetual war, fear, and amorality and that only government can hold a society together. He argued for the necessity and natural evolution of the social contract, a social construct in which individuals mutually unite into political societies, agreeing to abide by common rules and accept resultant duties to protect themselves and one another from whatever might come otherwise. His proposal however was not for a democratic order as we know it today instead, he proposed a strong central government, one with the power of the biblical Leviathan (a sea creature), which would protect people from their selfishness. Even though his prescription was not for a democratic order as we know it today, he acknowledged the need for cooperation within political societies.

However, Paleo-political anthropology studies [1] have demonstrated that, long before kingdoms and nation-states were established, our ancestors had found ways to cooperate for human survival whether as hunter-gatherers or as settled agriculturalists. It is these forms of cooperation that precede Greek philosophers who are said to have discovered democracy (see Mathews,). Fukuyama [2] writes; "Human beings never existed in a pre-social state. The idea that human beings at one time existed as isolated individuals, who interacted either through anarchic violence (Hobbes) or in pacific ignorance of one another (Rousseau), is not correct". Democracy is a social rather than a political term to refer to a society marked by equality of social conditions with no ascriptive aristocracy, and all careers open to all citizens including the opportunities to be in government (Tocqueville 1835). The kind of democracy under discussion is the one that assumes that no one of us will make the best decision for others-we have to figure it out for ourselves. In other words, democracy is about learning together.

Democracy is based on balancing power, making trade-offs, and ensuring civil liberties, and more importantly, it is about making sure that citizens are engaged in solving problems. These roles cannot be dispensed by an invested political elite alone, there is a need for broadening our understanding of how democracy works. Besides, not all the change needs to happen within government or led by government but most of the work of democracy is the work of citizens. The challenge in Zimbabwe and indeed in many other countries is that the idea of citizens is restricted mostly to voting and, in many cases, they are mostly referred to as voters. Voting is a necessary function within our democracy, but it is also not the only function of citizens. In other instances, citizens have been equated to the work done by non-state actor institutions such as NGOs, human rights groups, unions, etc. Non-state actor institutions are at a preliminary level indeed an expression of citizens' interest but over time a disconnect can also occur in which citizen interests remain at the periphery of what these institutions do.

There is a need for the emergence of a civic agency that is built through ongoing collective work where citizens begin to see themselves as co-creators of a new democratic governance framework. First, we must get beyond an overreliance on experts and begin to tap into various forms of knowledge embedded within communities. Boyte (2009:3) argues that 'we have to get beyond expert cults if we want to develop civic agency, the capacities of people and communities to solve problems and to generate cultures that sustain such agency'. David Mathews (2020), writing in a context of warning trust in the representative state system suggests that maybe this could be the time to reconsider Abraham Lincoln's ideal of a government of, by, and for the people in the Gettysburg Address to include governing with the people. According to Mathews a 'with' strategy encourages collaboration through mutually beneficial or reinforcing efforts between the citizenry and the government. It fosters collective work, not only among people who are alike or who like one another but among those who recognize they need one another to survive or to live the lives they want to live. In his formulation of the 'with' strategy, in which he describes complementary production fostering reciprocity between what citizens do and what governments do. The strategy is based on evidence that governments at any level can't do their jobs as effectively without the complementary efforts of people working with people.[1] That is because some things can only be done by citizens or that are best done by them. People aren't the only ones who need people democratic governments need working citizens. An instance of citizens' complementary production does not necessarily need to be organised through the state, but they produce public goods such as welfare, public safety, and food security which are otherwise traditionally provided for by the state.

Second, there is a need to make sure that there are adequate platforms for expression. Communities are unique. Individuals within different communities will build their civic agency based on the needs/challenges that they are responding to. There is a need to avoid prescriptive frameworks. Third, evidence from many studies has shown that individuals who are members of associations tend to be more interested in politics, better informed and to be more often involved in acts of political participation than people who are not members of such associations. Civic activism impacts the public arena positively because associations support the social infrastructure of public spheres that develop agendas, test ideas, embody deliberations, and provide voice. In almost every community (rural and urban) there is a mosaic of associational forms that includes loose unstructured networks such as civic engagement associations, residents' associations, neighbourhood watch committees, faith-based associations, loans, and savings associations, women's associations, burial societies, and professional associations are active across the length and breadth of Zimbabwe. These are the incubators of cooperation and democracy.

The associative activities take the form of popular local organisations, and their proliferation is based on the real needs, interests, and knowledge of the people involved. These flourish in any environment, even in areas that do not encourage independent association. There is a wide range of associational forms in both the rural and urban settings, including savings and loans societies, self-help organisations, multi-purpose cooperatives, occupational groupings, farmers unions, and, since the 1960s, rural-based NGOs. The leadership in these associations originates from amongst the concerned communities. Tocqueville (1840) notes that associations are the key features of democracy. When Alexis de Tocqueville visited the United States in 1832 he was struck by the vitality of its civic sphere: "Americans of all ages, all conditions, all minds constantly unite…". Tocqueville identified four different roles of associations as per the Table below:

Table 1-1 The Role of Associations

|

Role |

Descriptions |

|

Integrating |

They provide citizens an opportunity to develop norms of enlightened self-interest and the skills and habits of cooperation. The method of integration is horizontal working through social networks among equals rather than relationships of dependency |

|

Differentiating |

They provide space for individuals to form associations with distinct interests and identities. Provide a sense of community even for those who hold beliefs that are not accepted by the majority-mediating the tyranny of the majority opinion |

|

Capacity Building |

Citizens learn the skills and habits of collective action and organize themselves to accomplish great deeds |

|

Synergistic |

Reciprocal actions of man upon one another. Citizens in a democracy can exert social and political power rather than relying upon the power of great individuals. |

How can these formations contribute towards deepening the process of democracy? Very little has been invested in terms of working with these associations as part of a broader engagement on national and local democracy. Tocqueville's asserted that 'in democratic countries, the science of association is the mother of science'. However, although writing about a different context, John McKnight (2013:7) observes that 'no university has yet created a Department of Associational Science'. The Zimbabwean situation is very close to what is prevailing in other regions. In most instances, these voluntary associational forms do not feature within the democratization discourse, especially around big projects such as constitutional reform and elections. The potential synergy that can be derived through engaging local formations is underestimated especially within the realm of politics in government and civil society. They provide a platform for broad-based mass mobilization as we have seen in Latin America within the land movements and in former communist countries such as Poland where engaged citizens gathered under the banner of 'Solidarity' toppled a dictatorship. However, most analyses of the public space have unfortunately been devoted to the professionalized spaces dominated by donor-supported NGOs. These NGOs and other professionalized formations are not necessarily at the center of organic community mobilization and in many cases their consultative and consensus-building capacity is inadequate.

Following the pattern established by Ostrom and Gardener (1993:7) we propose to consider the different forms of cooperation that citizens forge with each other on an everyday basis and using Briggs' formulation consider this cooperation as part of problem-solving which contributes significantly to the texture of a democracy. We note that citizens and the formations they establish assume different roles ranging from cooperating with one another to strengthening prospects for economic survival/competitiveness, giving to each other, and confronting power.

Bibliography:

Barker, E. (2011). The role of associations. In J. Scott & P. Carrington (Eds.), The SAGE Handbook of social network analysis (pp. 196-214). SAGE Publications1

Boyte, H. C. (2009). Civic agency and the cult of the expert. Kettering Foundation1

Fukuyama, F. (2011). The origins of political order: From prehuman times to the French Revolution. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Hobbes, T. (1996). Leviathan (R. Tuck, Ed.). Cambridge University Press. (Original work published 1651) 1

Mathews, D. (1997). Politics for people: Finding a responsible public voice. University of Illinois Press

Mathews, D. (2020). With the people: An introduction to an idea. Kettering Foundation Press1

McKnight, J. (2013). The abundant community: Awakening the power of families and neighbourhoods. Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Ostrom, E. (1993). Covenanting, co-producing, and the good society. PEGS Newsletter, 3(2), 8.

Tocqueville, A. de. (2000). Democracy in America (H. C. Mansfield & D. Winthrop, Trans.). University of Chicago Press. (Original work published 1835) 1

Tocqueville, A. de. (2000). Democracy in America (H. C. Mansfield & D. Winthrop, Trans.). University of Chicago Press. (Original work published 1840) 1

The question of whether democracy has a direct relationship with the pursuit of inclusive economic development has been asked several times. Let us start with a quote from Venezuela's former President -Caldera.

It is difficult to ask the people to sacrifice themselves for freedom and democracy when they think that freedom and democracy are incapable of giving them food to eat, preventing the astronomical rise in the cost of subsistence, or placing a definitive end to the terrible scourge of corruption that, in the eyes of the entire world, is eating away at the institutions of Venezuela with each passing day.

As already stated, (see Introductory blog) democracy is in recession. According to Freedom House, democracy has been in recession for the past 15 years globally—a bit concerning for many of us. There are concerns with the resurgence of coups across Africa, rising intolerance of diversity and dissent, and exclusive nationalism. In many parts of Africa, election results are routinely challenged as not reflecting the will of the majority. Reports of arrests and torture of human rights defenders and governance activists have become part of daily reporting.

What shall we do? First things first- what if we are not naming the problem adequately? Yes, it is a problem of democracy- the constitutional type (see A Difficult Moment for Democracy, There Is Hope Part 2). However, the convulsions that we are seeing have to do with consumption and accumulation patterns. There are protests here and there about the failure to conduct elections properly. However, most of the protests that we mapped (https://africacitizenshipindex.org) have to do with poverty, jobs, corruption, police brutality, and rarely about elections or broad democracy. Are these issues unrelated to democracy? Perhaps, instead of focusing on increasing authoritarianism- what if we asked ourselves, ‘What else is happening in these countries where democracy is failing?

Could it be that they are the same countries associated with weak to non-existent economic growth? Everyday citizens rarely come out to say we are defending democracy (except maybe in America after the threats on Capitol Hill). In many instances, citizens come out to protest over the failings of the economy and specifically name the problems ranging from lack of jobs, increasing cost of living, lack of access to affordable health care, security, etc. On the face of it all these are problems of the economy and not necessarily the political system in place.

Could it be that democracy has been let down by the economic framework- especially the free market economy? Many countries that are going through various types of economic crises- have also found themselves confronting governance challenges that spring from how governments respond to citizen mobilisation (protests) or the realisation on the part of ruling elites that they may lose an election due to the failings in the economy. What then shall we fix, democracy or the economy? Others may say both. For many of us in Africa we have been seized with the infrastructure of democracy, developing, and adopting new constitutions, ensuring separation of powers, establishing independent commissions, and developing frameworks for the achievement of civil and political freedoms. Admittedly the process has been uneven, but we have made progress. At some point, the continent had managed to ‘silence the guns’ in terms of eradicating or reducing incidences of armed civil conflict and to agree on a consensus against coups. There is a strong democracy-oriented infrastructure within the African Union (AU).

However, challenges persist. Could it be that we have not paid sufficient attention to the attendant existing weakness within the economy? It is important to state that democracy has always been promoted together with a free market economic model. Most African countries conducted thoroughgoing economic reforms to align with free market thinking. Things got worse. Many jobs were lost in the civil service- it was argued that African governments had bloated bureaucracies- so they carried massive retrenchments and, in the process, rendered these bureaucracies ineffective. The small delicate steps towards industrialisation were crashed due to the insistence for liberalisation of trade and removal of tariffs. Retrenchments and company closures were the order of the day. For some reason, the same period was also associated with the growth of rapacious greed and corruption on the part of the political class. They moved from one scandal to the next- literally emptying state coffers and selling off strategic assets to ‘investors’ at rock bottom prices as part of the privatisation drive. The three decades of the free market have been nothing but disastrous for many. The benefits from the cited economic growth have not been widely shared. Instead, there are new Yachts and private planes owned by the elite thinly spread across the continent with properties in Dubai and offshore bank accounts. The middle class (driver of growth) has been thoroughly destroyed.

There was a brief hiatus- when China was growing at a breakneck speed. Many African countries benefited (in a limited way) due to China’s huge appetite for natural resources and agricultural products from Africa. However, China has since put brakes on its growth trajectory. Commodity prices have collapsed once again, and we are in an unprecedented economic crisis that is not only multifaceted but is taking place alongside and within the global economic crisis. The protests and civil unrests are back including military coups. Could this be an inflection point for both the economy and democracy here in Africa?

What shall we do?

Fixing democracy requires us to acknowledge its umbilical cord-like relationship with the economy. It is also an egg and chicken relationship-there is no clarity on which one should happen first. Others say fix democracy and the rest will sort itself. We have tried that and yet both are in disarray. Maybe let’s focus on simultaneously fixing both. Note that I am using ‘we’ and ‘us’ because I don’t believe this a project that can be handed over to governing and connected business elites. Citizens need to be engaged in the same way as we have been in the struggle for democracy.

There is an urgent need to rethink the characteristics of the economic model that will work. A foreign direct investment model will not work. African economies are required to urgently integrate value chains. Many countries depend on the export of primary commodities with no value addition despite the various studies that have demonstrated that this has ensured our continued impoverishment. Our agitations should be for the establishment of industrialisation and innovation funds that are managed transparently. In the interim, governments need to come up with a more effective taxation system. Africa continues to lose over $20 billion annually through illicit financial flows. In many instances what is derogatorily referred to as the 'informal sector’ is the equivalent of the cottage industry in other countries except that in many African countries players in this sector have never received an incentive from their governments. Yet the same sector has the potential to be the largest employer in countries beset by low levels of industrialisation. However, we continue to shun it and keep it out of formal financial circuits. There are many other low-hanging fruits and long-term suggestions for fixing the economy.

There is an urgent need for working economies that can address issues to do with increasing unemployment, inflation (erosion of incomes), weak social service delivery, and unjust patterns of economic extraction and accumulation. The alternative is too ghastly to contemplate but can be summarised in one word- COLLAPSE. We cannot fix democracy when the economy is in disarray.

Last week on Friday, we (www.sivioinstitute.org) launched our 2023 signature initiative-AfricaGiving (www.africagiving.org). It has been a long and challenging but exciting journey to get here and there is still a long journey ahead. AfricaGiving is many things to different people, on the one hand, it is about our culture, and what defines us as a people. Bheki Moyo and Tade Aina in their seminal edited book summarised our existence elegantly as comprising of ‘giving to help and helping to give.’ We go a step further and suggest that giving is our essence-we give to live and live to give. Perhaps this is best encapsulated in the norms of Ubuntu- I am because you are. African Giving speaks of our interdependence on each other- perhaps affirming the English saying that no man/woman is an island. Our lives and our destinies are interconnected. We are known as a people of warmth, love, solidarity, and resilience. We have carried the world before, and we still do. For indeed there are many more resources that leave our shores than those that flow in. We have it in our stride to soldier with the little that we share amongst ourselves.

However, there is an unsettling in our bellies. A rumbling of sorts. That we are also good enough. We cannot live on the crumbs from the Master’s table. Since the turn of the century, we have seen a new and reinvigorated passion not only to change Africa but the world. We do not only export products we export culture, Afrobeats, Amapiano, but African storytelling in movies also made here in Johannesburg, Cape Town and Nollywood. Our sons and daughters are filling stadiums in far-off lands. We may just have arrived on the scene, but we are shaking the world. Our entrepreneurs are changing the African business landscape in profound ways. We now talk of a list of Africa’s own billionaires, from Patrice Motsepe, Strive Masiyiwa, Aliko Dangote and many others… We are building strong African brands. It is perhaps Africa’s time.

There are urgent challenges as well. The number of the poor is not slowing down. It is growing. Inequality - the gap between the rich and the poor is widening. Our success is not widely shared. There are more children living below the poverty datum line, our future- the youth- are dying trying to cross the treacherous seas to make a living in places where they remain unwanted. Nineteenth-century diseases like Cholera are making an unwelcome return to our cities. We risk leaving so many behind in the effort to increase Africa’s prominence on the global stage.

What are we to do? Could this be the time to complain about how our governments are failing us? Or how the international community has let us down? Have we not done enough complaining already? What if now is the moment for us to pull together in solidarity as a people? What if we seek to reconfigure the limitations of our civilisation by challenging received wisdom which has placed a premium on accumulation and very little on giving? What if we considered a new paradigm of shared responsibility- it is not up to the government alone, but it is our responsibility to create conditions of inclusive societies. Can we revisit that moment in history when success was not only about profit but included the extent to which we cared for each other? Is there a way of measuring success- beyond the usual net worth towards a more comprehensive understanding of what we do with our time, skills, and resources to help lift others out of poverty? A little kindness goes a long way. Over the years we have listened to titans in industry, politics, and other spheres of the economy and without fail they always refer to that moment when there was a helping hand at the beginning of their journey.

The world requires more kindness than before. Today we celebrate sprinklings of kindness. The few amongst us whom we celebrated through the awarding of the inaugural AfricaGiving awards have turned logic on its head when it comes to money. Instead of keeping it, they have been giving it away. They have not only given money, but they have also been in the trenches fighting and believing for a better world. We applaud their love for humanity. We are humbled by their energy and commitment to a better world.