An overview of my blogging journey in 2024

I have used the blog form of writing for a while now to share insights from my research with a broader audience. In 2024 I published twelve blog posts covering various themes, including democracy, development, agrarian reforms, and personal development. While the responses have varied, my letter entitled "Dear Dalitso" has garnered the most interest. In this overview, I have taken the opportunity to reflect on my blogging journey month by month and to compile all the links to each blog in one convenient location for the reader's ease of access.

In February, I published a blog titled “ The Big Bet”. 2024,” which sparked significant discussion among colleagues. The blog has reached 133 views, while the accompanying podcast has garnered 223 views. It critiques the diminishing emphasis on community assets in development discourse, which is often overshadowed by state behaviour. The central argument is that engaged citizens, and local associations are vital for fostering democracy and inclusive development. In this blog I argue against reducing democracy to mere electoral events, emphasizing that true democracy involves public problem-solving across society. Observations from Zimbabwe, Malawi, and Zambia reveal that government performance frequently falls short of citizens' needs, perpetuating poverty, and inequality. However, communities show resilience through both informal and formal networks of solidarity, essential for resource pooling and addressing local challenges. The blog advocates for a renewed focus on community associational life, highlighting grassroots efforts to enhance accountability and improve livelihoods.

I then worked on a series of writings titled the "Democracy and … Series during which I explored various aspects of democracy, all of which were composed from March 7th to March 10th. The inaugural publication in this six-part series highlights a pressing global consensus, how democracy is in decline while authoritarian regimes are gaining strength and solidarity. This troubling trend is underscored by the 2020 Democracy Index from the Economist Intelligence Unit, which revealed that only 49.4% of the world's population lives under some form of democracy, with only 8.4% in "full democracies." The series calls for critical reflection on this decline, particularly in Africa, where military coups, one-party rule, and authoritarianism prevail. It points to public dissatisfaction driven by corruption and ineffective governance, arguing that mere elections are not enough. Genuine democracy requires enhancing public freedoms, citizen engagement, and equitable resource distribution. The series seeks to explore ways to revive democratic ideals, emphasizing democracy as a continuous societal commitment rather than just an electoral event.

Let’s Talk About Democracy: A Definitional Crisis dives into the pressing concerns surrounding the perceived threats to democracy in an era marked by rising authoritarianism globally. I highlight significant challenges to established political and governance frameworks, including events like the attempted coup in the United States, the rise of right-wing nationalism, and a resurgence of military coups, alongside China's growing influence. I argue that these issues may signal a crisis in how power is exercised, often benefiting a select few. It outlines three democratic frameworks—consensus, constitutional, and deliberative democracy—highlighting the importance of citizen engagement. Despite the threats, grassroots movements and global citizen initiatives offer hope for revitalizing democratic practices. I make a call for a reimagining of electoral systems to reflect the will of all citizens, promoting a more inclusive and equitable democratic future.

In my blog, “Democracy and…The Principle of Adequate Representation” I dive into the evolution and challenges of democracy, tracing its origins to Ancient Greece, particularly the reforms of Cleisthenes, who established citizenship as the basis for political responsibility rather than clan affiliation. Although this shift enabled broader participation, it also led to early exclusionary practices based on wealth and education. I argue that despite democracy's connection to the French Revolution and universal suffrage, achieving meaningful representation remains difficult due to social cleavages such as race, language, and gender. Focusing on Zimbabwe, I critique local representation hampered by tribalism and the disconnect between leaders and constituents. I advocate for an inclusive approach that genuinely reflects the interests of marginalized groups like women and youth, urging political parties to go beyond superficial practices. Ultimately, the blog underscores the necessity for a participatory democracy that addresses community-specific challenges through evidence-based policy-making and grassroots engagement.

In my fourth piece, "Democracy and the Principle of Effective Participation " I highlight the importance of citizen participation in democracy. I argue that effective governance relies on amplifying local voices, upholding the rule of law, and fostering equity. I define citizenship as active engagement in governance rather than mere legal status. Despite Zimbabwe's constitutional mandate for inclusive participation, I pointed out numerous challenges citizens face in engaging with their government. While mechanisms like public protests and local consultations exist, genuine participation often feels elusive due to perceived powerlessness and superficial frameworks. For further exploration, I discussed these themes on the podcast “What If - What If There Is an Alternative: Is Participation the Missing Key?” which received 173 views, highlighting its relevance.

"Democracy and the Principle of Cooperation," addresses critical issues surrounding the evolution of political systems and the role of civic engagement in democracy, particularly in the context of Zimbabwe. I critique the traditional view of democracy as merely a function of voting, emphasizing that true democratic engagement requires active citizen participation beyond electoral processes. Drawing on historical perspectives from thinkers like Thomas Hobbes and Alexis de Tocqueville, I argue that democracy is inherently a social construct that thrives on cooperation and collective action among citizens. I also highlight the importance of civic agency, which can be cultivated through grassroots associations that reflect the unique needs and challenges of communities. These associations not only foster political participation but also serve as incubators for democratic values and practices. Furthermore, I underscore the necessity of a 'with' approach, i.e. government working with citizens to enhance mutual efforts between state and society. I then call for greater recognition of local associative forms as vital components in deepening democracy, suggesting that these grassroots movements can significantly contribute to national discourse on governance and civic responsibility.

In the sixth instalment of the “Democracy and…” series, titled "Democracy and the Principle of Economic Inclusion: Part One," I delve into the critical intersection of democratic governance and economic inclusion. I address the decline of democratic values during economic crises, citing a 15-year trend of democratic recession, particularly in Africa, where coups, intolerance, and human rights violations are rising. I also argue that many public protests are driven by economic grievances rather than demands for democracy. While acknowledging progress in African democratic frameworks, I identified persistent economic weaknesses that hinder true democratic development. I also criticized free-market models for increasing job losses and inequality, widening the gap between elites and the majority. Advocating for a reassessment of economic strategies, I call for integrated value chains, innovative funding for industrialization, and greater citizen engagement in reform efforts, moving away from reliance on political and business elites. I then concluded by stressing the urgent need for an inclusive economic framework to support democratic values and tackle issues like unemployment and inflation.

On July 20, 2024, I published a blog titled "AfricaGiving-More Than Just an App!" that examines the work of our innovative AfricaGiving app, which my organisation, SIVIO Institute launched in 2023, on the African philanthropy landscape. This innovative platform seeks to address the challenges local non-profits face in securing sustainable funding and visibility while emphasizing the need for a change in basic assumptions in philanthropy. It facilitates direct giving across diverse contexts, strengthens organizational governance, and fosters trust through rigorous vetting processes. I note the importance of building relationships between individual donors and organizations, advocating for a cultural shift towards online giving. The blog also highlights the successful "100 for $100" campaign, showcasing the app's capacity to connect donors with meaningful causes and promote collaborative philanthropy. Overall, AfricaGiving is positioned as a crucial tool for enhancing community-driven initiatives and nurturing a culture of giving in Africa.

On July 23, 2024, I published a blog titled "South Africa’s Elections Are a Warning Sign for Democracy," featured on the Kettering Foundation website. This analysis, following the May 2024 national elections, examines the African National Congress's (ANC) decline, as it secured only 40.2% of the vote—the lowest since 1994. I highlight voter disillusionment due to the ANC's unfulfilled promises and internal divisions that led to breakaway parties capturing 24.1% of the vote. I caution that without a renewed focus on inclusive economic development and effective governance, South Africa's democracy is at risk. The blog emphasizes the urgent need for the ANC to tackle governance issues, corruption, and rising inequality to preserve stability and democratic integrity.

Fifteen days after Rwanda's elections (30 July 2024), Nyasha McBride Mpani and I published an article titled "Freedom of Choice in Rwanda’s Presidential Elections is an Illusion," in Mail & Guardian. The analysis critiques the political situation following President Paul Kagame's 99% vote win, questioning the legitimacy of such results amidst his long-standing presidency since 2000 and the lack of viable alternatives for voters. We contextualize Kagame's popularity within Rwanda's post-genocide recovery, comparing it to the ongoing struggles in countries like Zimbabwe. We express concerns about political dissent suppression, exemplified by the imprisonment of opposition figures like Diane Rwigara, complicating the electoral transparency debates. Ultimately, we argue that despite Kagame's contributions to stability and development, Rwanda still lacks genuine public participation and political pluralism, challenging the nation's quest for effective governance alongside democratic freedoms.

In the article "Latest Developments on Land Tenure Reforms in Zimbabwe," published on October 10th, 2024, I examine the Government of Zimbabwe's announcement on land tenure changes for fast-track farms, which introduces bankable titles allowing landowners to borrow against, sell, or subdivide their property, with restrictions on sales to 'indigenous' citizens. The blog discusses the potential benefits, such as improved financing, enhanced agricultural productivity, and a new land market, while also addressing challenges like land concentration and the need for effective governance to tackle issues with land barons. My dedication to land and agrarian issues is evident in my previous works, which serve as valuable resources for enthusiasts seeking to explore these topics further. These include the policy brief "To Compensate or Not To? Revisiting the Debate on Compensation for Former Large–Scale Farmers in Zimbabwe," the policy insight "titled The Past in the Present: Challenges of Protecting Customary Tenure Provisions - The Chilonga Case," and the article "titled Exploring The Tenure- Nexus on Customary Land Right Holders ." Additionally, I explored the impact of land reform on agricultural practices in Zimbabwe through the What If Podcast,where I examined the impact of land reform on Zimbabwean agricultural practices nearly 25 years post-fast-track implementation, discussing the necessity of these reforms and potential future pathways for the sector, which has garnered 126 views and is available on Spotify and Apple Podcasts. The discussion emphasizes the necessity of these reforms and future directions for the sector.

On December 24, 2024, I concluded the year with a blog titled "2024: The Year Democracy Was Tested in Africa," originally featured in Mail & Guardian. In this analysis, I distill the critical issues surrounding democratic governance across the continent, highlighting the significant costs of conducting elections in Africa, averaging $4.20 per capita—double the global average. Increasing public scepticism towards electoral commissions, coupled with a demand for accountability, underscores the electorate's impatience for substantive change rather than mere power shifts among elites. The blog also discusses the ideological evolution in African politics, with a shift from personality-driven politics to performance-based assessments of governance. While there are signs of deepening democratic practices, a concurrent rise in authoritarianism poses a threat to progress. I argue that elections alone are insufficient for true democracy, emphasizing the necessity of broad citizen engagement and governance focused on development rather than perpetual electoral cycles.

These are just my views based on various readings and field research. The only conclusion I make is that democracy is a work in progress. It is not necessarily about elections but more about citizens engaged in fixing public problems collectively. The year ahead is going to require even more work from all of us. At times, we restrict ourselves to focusing only on who to vote for; that is important, but we need to go beyond that. How else can we contribute towards the change that we desire?

For more information on my writings, visit

What do Zimbabweans Want?

What do Zimbabweans Want?

Tendai Murisa

There is a raging debate on social media platforms surrounding Winky D and Holy Ten’s song ‘Ibotso’. In the song the musician raises issues to do with social injustices that perpetuate inequality, where the taller(strong) ones forcibly grab resources from the short (weak) ones. It’s a song that can be played in almost any country and it would resonate with the plight of the downtrodden. The conditions of poverty and growing inequality aptly described in the song are not a figment of the musicians’ imagination.

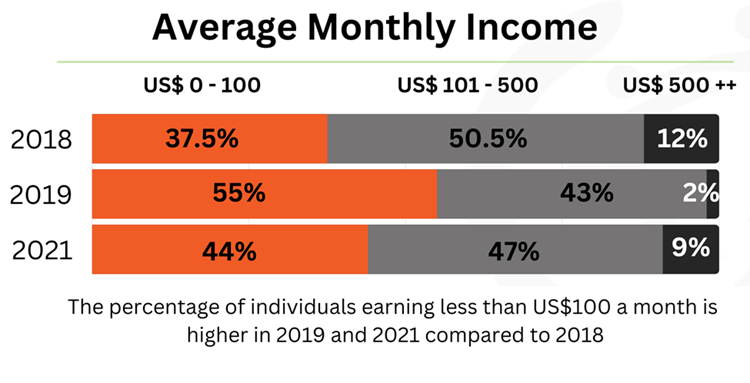

Evidence from field surveys carried out over a period of three years demonstrates that socio-economic conditions have worsened in the past three years or so due to several factors such as COVID-19 related lock down measures, droughts, contraction of the economy (also partly due to COVID-19). Findings from our nationwide surveys carried out in 2018, 2019 and 2021 indicate that there has been gradual decrease in average incomes and a consequent increase in the number of those who are employed in the informal sector.

Figure 1

The trends described above paint a picture of growing conditions of poverty. Yet officeholders in government make claims of progress. Some of the claims cannot be contested. Indeed, the government under President Mnangagwa has pushed an infrastructure led approach to transformation. The infrastructure projects include dams (one in every province), refurbishments of major roads (near completion of the Beitbridge to Harare highway), building houses, resuscitation of irrigation schemes and driving modernization of agriculture. The government revised downwards its target of 1million houses to 250,000 and as of August 2022 the Minister of National Housing and Social Amenities outlines that significant progress has been made on 140 housing units and 8 blocks of flats (Post Cabinet Press Briefing – August 2022). Despite all these notable achievements there is still a strong feeling that government has not delivered on its electoral promises of rapid and inclusive economic recovery. The general conditions of poverty, acute food insecurity, lack of employment, increasing cost of living remain the order of the day. There is general despondency about livelihoods in the country. Assumptions within government were that the benefits from the infrastructure driven development model would ‘trickle down’ to benefit the majority. However, evidence from other regions has already demonstrated the ineffectiveness of the ‘trickle down’ theory. Rather the infrastructure led approach has contributed towards growing inequality through the emergence of a new state linked business class. It is this business class that has benefitted the most from government’s spending on infrastructure and explains how young businesses such as Fossil are able to successfully bid for a large company such as the cement maker Lafarge.

The trends described above paint a picture of growing conditions of poverty. Yet officeholders in government make claims of progress. Some of the claims cannot be contested. Indeed, the government under President Mnangagwa has pushed an infrastructure led approach to transformation. The infrastructure projects include dams (one in every province), refurbishments of major roads (near completion of the Beitbridge to Harare highway), building houses, resuscitation of irrigation schemes and driving modernization of agriculture. The government revised downwards its target of 1million houses to 250,000 and as of August 2022 the Minister of National Housing and Social Amenities outlines that significant progress has been made on 140 housing units and 8 blocks of flats (Post Cabinet Press Briefing – August 2022). Despite all these notable achievements there is still a strong feeling that government has not delivered on its electoral promises of rapid and inclusive economic recovery. The general conditions of poverty, acute food insecurity, lack of employment, increasing cost of living remain the order of the day. There is general despondency about livelihoods in the country. Assumptions within government were that the benefits from the infrastructure driven development model would ‘trickle down’ to benefit the majority. However, evidence from other regions has already demonstrated the ineffectiveness of the ‘trickle down’ theory. Rather the infrastructure led approach has contributed towards growing inequality through the emergence of a new state linked business class. It is this business class that has benefitted the most from government’s spending on infrastructure and explains how young businesses such as Fossil are able to successfully bid for a large company such as the cement maker Lafarge.

In the process government has neglected spending on social service delivery, despite growing evidence that increased allocations for the social sector (especially education, health, and housing) contribute towards equitable development. Education still provides the most reliable pathway out of poverty in other stable environments. Conditions of employment in the health and education sector continue to worsen. Hospitals are understaffed with an acute shortage of essential drugs and functioning equipment. Teachers, like their counterparts in the health sector, are poorly remunerated. There is a real fear that the country will experience an exodus of teachers to the United Kingdom (UK). Recently the UK announced that it will be recruiting teachers from Ghana and Zimbabwe to deal with its own shortages. There are no incentives to keep teachers in the country.

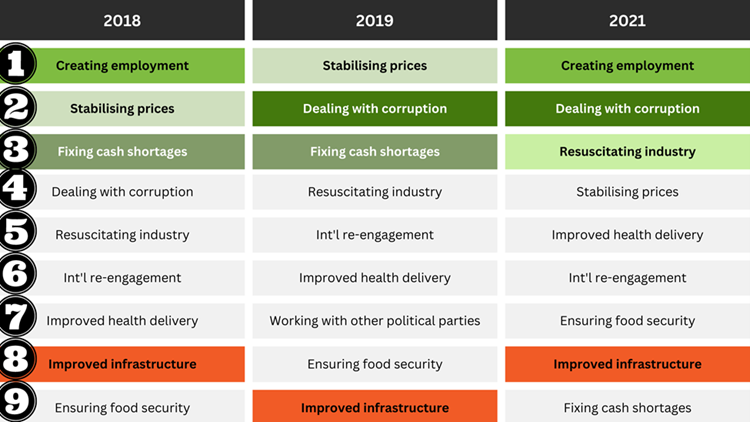

However, if the government had bothered to listen to citizens (electorate)-they could have done things better. Since 2018 we (www.sivioinstitute.org), have been conducting surveys across the country asking citizens to identify issues that they expect their government to prioritize. We found in 2021 that on average citizens are mostly concerned about; creation of employment (44%), effective resolution of the problem of corruption (40%), resuscitating industry (33%) and stable prices (32%). Outside of these major concerns citizens expect government to focus also on improved local government service provision (11%), improved provision of education (11%) and affordable housing (9%). In other words, the electorate expects government to be seized with devising economic strategies that ensure equitable development and deal with other vices such as corruption. The table below provides a list of issues, in order of priority, that citizens expect government to focus on. There is no doubt that the modernisation of infrastructure is important, but it does not rank highly amongst citizens. In 2018 and 2021 it ranked 8th whilst in 2019 it ranked 9th.

Table 1: Citizens Top 3 Expectations of Central Government

Source: Citizens Expectations and Perceptions Survey SIVIO Institute

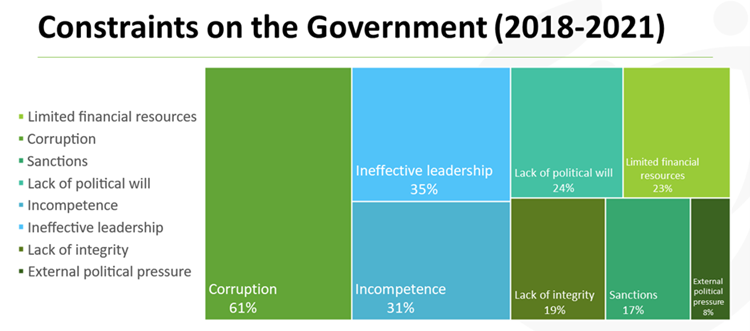

Furthermore, the citizens have an idea of factors that are impeding progress or achievement of a better socio-economic order. These include corruption (61%), ineffective leadership (42%), incompetence (37%). These were the top three factors limiting government performance identified by citizens across all the 3 surveys. Sanctions do feature on the list of factors constraining government performance but are ranked 6th.

Figure 2

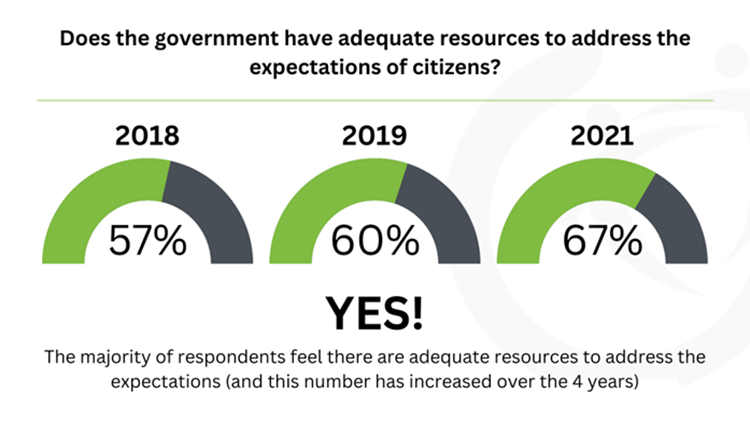

While 22% do consider limited financial resources to be a constraint to government performance, the majority (67%) of the respondents in 2021 (figure 3) also think that government has sufficient resources to affect a more equitable framework for development.

Figure 3

Finally, success for citizens means the re-opening of industries (55%), functional clinics and hospitals (48%), arresting of those engaged in corruption (46%), well-paying jobs (28%), re-engagement with the international community (18%), food security (11%). Perhaps the question to be asked is the extent to which the government has fared in terms of achieving the above listed milestones of progress. For many there is little that has changed. Could it be that government has become its own worst enemy. At the beginning of his term the current President assured citizens that he will be a listening president. The divergence between policy and citizen expectations suggests otherwise.

Finally, success for citizens means the re-opening of industries (55%), functional clinics and hospitals (48%), arresting of those engaged in corruption (46%), well-paying jobs (28%), re-engagement with the international community (18%), food security (11%). Perhaps the question to be asked is the extent to which the government has fared in terms of achieving the above listed milestones of progress. For many there is little that has changed. Could it be that government has become its own worst enemy. At the beginning of his term the current President assured citizens that he will be a listening president. The divergence between policy and citizen expectations suggests otherwise.

Government is operating as a silo without a feedback loop. Unfortunately, the era of top-down and expert led policy making without widespread consultations is over. There is need to consider new approaches to governance which include co-creation and co-production. Government’s approach has been to ‘surprise’ people with important policies starting with the transitional stabilisation programme of 2018. At the time of its launch there was no record of any consultations with important stakeholders including business. In many instances policies are rejected not necessarily because they are bad but most often it is because they are being imposed on the people. Government needs to embrace co-creation of policies and strategies as a value.

Furthermore, it is widely recognized that government does not have the wherewithal to fix every public problem withing the country. Practice elsewhere suggests the need to view citizens not only as voters but as co-producers of public goods. Citizens, in their individual and corporate capacities, have amply demonstrated their capacities to contribute to national development through multiple strategies that entail providing for or supporting government’s efforts in service provision. However, currently bureaucratic red tape has only served to frustrate citizens’ collective agency. Is it not ironic that a country struggling to provide adequate healthcare and other social goods is actively pursuing efforts of limiting citizens agency through various measures including passing a draconian law on private voluntary organisations. NGOs, Unions, Associations, community-based organisations have made immense contributions towards creating social safety nets for the vulnerable. Yet today their future is uncertain. There are very few instances where a ‘government alone’ approach has ever adequately contributed towards inclusive and equitable development. Government needs other partners to make a dent on growing poverty and growing inequality.

The forthcoming battle for office will largely be about livelihoods. It is our hope that would-be officeholders will spend more time trying to understand what citizens want. The response to Winky D and Holy Ten’s song demonstrates the contestations that exist between on the one hand the small band of those benefitting from the status quo and are seeking to defend their privilege and on the other hand those who are genuinely feel left behind and excluded the state led neo-liberal model currently at play in the country. The musicians have only captured the mood in society. People are concerned about abuse of power, increasing levels of corruption, improved access, ineffectiveness of the preferred development model and declining quality of social goods. These are part of everyday discussions. Let’s remember Queen Marie Antoinette in 1789 who in the face of bread riots asked if the rioters cannot be given cake instead. It is our hope that in 2023 our leaders are not so distant from the social and economic realities of Zimbabwe not to recognize the major crisis that we are dealing with. Ibotso!

NB: This article was originally published in The Zimbabwe Independent 20 Jan 2023. (https://www.newsday.co.zw/theindependent/opinion/article/200006369/what-do-zimbabweans-want)

To Compensate or Not to - A Discussion Note

This Flag: A New Citizen Based Politics and Discourse

My Thoughts on Xenophobia

My Reflections

The acts of violence that recently swept across South Africa against foreign nationals have once again brought to the fore questions of identity, nation and what it means to be African. I have followed the news and read several commentaries. Achille Mbembe and Trevor Ncube have been some of the brave non-South African voices that made a contribution based on their experiences of the different manifestations of xenophobia or, more specifically, Afrophobia, as they would like to call it. These and others have been very helpful for those of us tracking issues from afar, but I feel that there is still something behind the story that is not being discussed. The dominant arguments/refrains can be classified within the three clusters, and I will show that these have become rackets in themselves not challenging us on how we can collectively overcome the challenge we face. In other words, they provide us with a comfortable lens of looking at society without necessarily hearing the concerns of others. I think the brothers and sisters of South Africa who took to the streets and engaged in violence have some form of a grievance, and there is need for a genuine audience to listen and take up their issues.

In summary, we have 3 dominant strands of arguments; (i) foreigners are taking our jobs and they must go back, (ii) Africa also contributed to the dismantling of apartheid, and (iii) related to (ii), we are all Africans and we should learn to live and coexist together. The ‘foreigners are taking our jobs’ position is statistically valid but it also ignores other dimensions such as skills matching, desirability of the jobs that foreigners do, and also acceptability of the wages that foreigners get. In a context of high levels of unemployment, this will always come up and should not be easily dismissed. The second position, that Africa contributed towards South Africa’s liberation, is very true despite some recent attempts to wipe away African countries and their regional blocs’ solidarity in the dismantling of apartheid. Lives were lost, economies disrupted and other political leaders were sidelined because of their commitment to the liberation of South Africa. However, I do not think we made that contribution so that we can go and settle in South Africa. It was our way of standing with fellow African brothers and sisters who were under an evil system of rule. We also look back on that day in 1994 when South Africans were allowed to vote with pride and celebrate Freedom Day on the 27th of April. In brief, we made a contribution so that a fellow African nation could have majority rule and her people could have the dignity of being able to choose their leaders. There should be no debt for such acts of solidarity and South Africa is not the only country that received such solidarity. The third strand of the common arguments is that we are all African and we should be able to co-exist, and we are embarrassed by what our fellow nationals are doing to others. If I were South African, I would probably belong to this cluster, which makes a lot of sense, but sadly does not address the first question as to why people are engaged in violence. Reminding those engaged in, or supporting violence against foreign nationals that the person they are killing or planning to kill is also an African like them makes it seem as if they had forgotten or were not aware of that fact. I do not think so. They are very aware that they are about to kill a fellow human being. It is an expression of deeper rage.

Sadly, these three clusters of arguing do not bring us anywhere close to a solution except maybe pushing for punitive sentences for those caught organizing and engaging in violence. Then what? Have we addressed Xenophobia for good? I think we should really think about a more systematic and long-term process to deal with this issue. All of us, and not just the South African government. Here I think President Zuma’s question, paraphrased to read ‘… why are all these foreigners here’, provides us with an opportunity to be a bit more rigorous in trying to address the matter.

My starting point is that the acts of violence are being done in the name of jobs and economic well-being. Foreign nationals are seen as dipping too much into the national cake at the expense of nationals. Then, we need to look at historical patterns of production and accumulation, and how foreign nationals have historically contributed to the South Africa economy. Historically, South Africa has always benefitted from migrant labour, especially to work on the farms and mines. Labour recruiting stations for South African mines were established across the sub-region. Migrant labour was mostly underpaid and not accorded present day rights and privileges that the unions are demanding. The official process of recruiting foreign nationals to service the needs of mines and farms may no longer be existent, but it continues through informal means and continues to serve the profit maximization goal of capital. In the end, we have massive exploitation of labour with disastrous consequences, as in Marikana. In fact, any attempt to look at acts of violence against foreign nationals living in townships as separate from the struggles for better pay and better jobs is misguided. There is a close relationship, but the gap in articulation is mostly because of the manner in which the working poor are organized or disorganized. It is the logic of capital accumulation that is under scrutiny. Why do businesses prefer to employ foreigners? It is not because they work better. That is just patronizing. It is because they are not unionized and can be easily underpaid with no recourse for complaining.

Secondly, when South Africa attained independence in 1994, expectations were high that with the removal of colonization and apartheid the sub-region was now ready for regional integration. Indeed, by then, the SADCC had become a model of integration for other sub-regions, such as the East Africa block and the West Africa block. But instead, efforts at economic integration in Southern Africa have slowed down. South Africa has played a major role in the sub-region, but its focus has mostly been in ensuring stability through facilitating dialogues, quelling coups and peacekeeping. Pretoria’s budget for diplomacy across the Sub-Saharan Africa is probably the biggest. However, most of South Africa’s focus has not been towards social and regional integration, which was originally the hope of the Frontline State, and the precursor to SADCC, but instead on ensuring stability to allow business to operate with no disruptions.

It is important to bear in mind that South Africa is a sub-imperial force and an important intermediary for international capital. It has worked within that logic, ensuring that the sub-region has peace and stability, and intervening where her economic interests are under threat, for example, in Lesotho. It has not taken advantage of its advanced economy to pursue a regional integration model that ensures wider and equitable growth but has instead pursued and defended her economic interests, working closely with its representatives of capital. It is telling that during one of President Zuma’s first trips into Africa, covering Angola and DRC precisely, he was accompanied by businessmen with interests in mining and agriculture. Since the late 1990s, South African-financed shopping malls, housing mostly South Africa retails shops and supermarkets, have become a permanent landmark not only in Southern Africa, but all the way to Accra, Ghana. In the extractive sector, South African owned/aligned mining houses have pursued a similar model of extracting primary commodities with limited re-investment in down-stream and side-stream value chains. In some cases, these companies use mostly South African labour on six-week rotations. In brief, South African companies have pursued an FDI model into Africa without reforming exploitative patterns inherent in global accumulation processes or at the very least attending to the concerns of their fellow Africans.

Many African countries are currently experiencing very limited prospects for the growth of their national savings accounts because, despite widespread GDP growth, the share resources going to locals, in terms of Gross National Income, is very insignificant thanks to investors like South African companies that are quick to repatriate their profits. Trevor Ncube laments the fact that South Africa did not play a decisive role in constraining Mugabe in Zimbabwe. I see it differently. That was probably never their objective. Instead, they had huge economic interests. One of the immediate outcomes from the South African negotiated Government of National Unity was the awarding of a contract to resurface Zimbabwe’s major highway from Plumtree to Mutare via Bulawayo and Harare. The contract was awarded without going to tender on a build, operate and transfer (BOT) basis, despite the fact that there has been a consortium of local businesses asking government for a similar deal. I am sure there are many other cases across the continent. I would like to submit to you, Mr. President, that the answer to your questions is these are ‘chickens merely coming back home to roost’. If other non-South-African economies are not growing, labour will continue to flock to Egoli!

To be fair, South Africa is not entirely responsible for the mess we are in. The governance records of many African countries leave a lot to be desired, but that may distract me from my main argument, which is the role of South Africa in the continent and in particular Southern Africa. I have already stated that South Africa takes a sub-imperial approach. This simply means that it does not have the same capacity of an imperial power like the USA, for instance, but is in a position to act as an intermediary for imperial powers. For example, South Africa’s membership into the BRICS group is not mostly because she is an economic powerhouse, which she is. But, it is also because it has the capacity, as South African Airways puts it, to ‘take Africa to the world and the world to Africa’. It provides an excellent launching pad for many would-be investors into Africa, and also takes advantage of her influential position in both the SADC and at the AU to ensure a conducive business environment. South Africa has chosen to subordinate itself to the dictates of international capital and preserve the status quo beyond its borders on behalf of business rather than being the champion of the developing region.

Now, what is to be done? The first imperative is to create jobs. Honestly, this is a no-brainer. The doomsday prophecies about the collapse of the Rand will always be there. But, without the ANC taking on leadership and taking a developmental state position, they can only work on the margins and tinker with welfare reforms which, in themselves, could be a disincentive for economic growth. Beyond that, I will not meddle into the murky waters of national economic policies.

Currently, the SADC is engaged in an attempt to roll out an industrialization strategy. Although not yet expressed officially, everyone knows that the success or failure of the program rests squarely on South Africa. Is South Africa interested in a program that will assist member countries to develop industrialized capacity, which may potentially reduce their dependence on goods imported from South Africa? We will see. Potentially, the creation and rolling out of an industrialization strategy that benefits from agriculture and mining could create millions of job across the sub-region, thereby lessening the lure of crossing the Limpopo in search of greener pastures.

Yes, there are other short-term measures that could be taken, such as improving border patrols, reducing corruption within the department of home affairs, and fining businesses that employ undocumented foreigners. I would like to submit to you that at some point in the life of a government, lethargy will set in and foreigners will still descend on your shores. Help African countries grow their productive capacities. In other words, create incentives for people to stay in their countries.

Furthermore, this matter should not be treated as an isolated event or as South Africa’s unique problem. It is systemic and regional in nature. Those calling for a conference/summit on this matter are absolutely right. South Africa’s current diplomatic efforts, through sending ministers to different African capitals, are commendable. But, that is just for the moment. In the absence of a coherent South African and regional strategy, this is like patching together a badly damaged road while waiting for the next rains to see what happens. We do not know how it will resurface, but I can assure you it will, if nothing is done. And next time, it may not just be the seven lives we counted in this round. We should also take cognizance of the shifting political interests. What if, the next time, the ANC government is in support of this as the cause of economic stagnation and lack of jobs? Let me give you an example. Zimbabwe has, since the 1980s and well into the 1990s, experienced some levels of grassroots based organized violence against predominantly white farmers, although, thankfully, there were no murders, but mostly disruption of production right up until 2000. Then all of a sudden, the tone of government changed from condemning these skirmishes to endorsing them as a genuine grievance mostly because ZANU (PF)’s political fortunes were declining. I hope we will not have such parallels in South Africa.