There is a new consensus, democracy is on the decline and authoritarian regimes are consolidating, expanding and exercising solidarity with each other. Could this be the moment for a post-democracy compact or the reinvention of democracy? A lot has already been written about this subject- see for instance the Pew centre report on dissatisfaction with democracy here . According to the Democracy Index published by the Economist Intelligence Unit, the 2020 global average score for democracy fell to its lowest level since the index began in 2006. The same report cited above provides a snapshot of global patterns as follows.

…only about half (49.4%) of the world’s population live in a democracy of some sort, and even fewer (8.4%) reside in a “full democracy”; this level is up from 5.7% in 2019, as several Asian countries have been upgraded. More than one-third of the world’s population live under authoritarian rule, with a large share being in China.

In the 2020 Democracy Index, 75 of the 167 countries and territories covered by the model, or 44.9% of the total, are considered to be democracies. The number of “full democracies” increased to 23 in 2020, up from 22 in 2019. The number of “flawed democracies” fell by two, to 52. Of the remaining 92 countries in the index, 57 are “authoritarian regimes”, up from 54 in 2019, and 35 are classified as “hybrid regimes”, down from 37 in 2019.

However, many writings including the reports cited above do not adequately interrogate how we got here. There is a need for an urgent and a somber reflection in order to move forward. There is an ongoing project of examining present day challenges of democracy across the world, see for instance the work of Freedom House, Kettering Foundation, and many others. The overall concern in most of these platforms is based on the real decline in the number of countries that fit the tag of being called a ‘democracy’. In Africa, the concerns around the collapse of democracy are manifest in at least three ways- the return to military led coups, the entrenchment of one-party rule through manipulations or mutilations to the constitution and subtle authoritarian creep using state resources to buy off the opposition.

There is an increasing number of surveys where respondents have confirmed their dislike for the current status quo around democracy due to corruption amongst the elites and failure of the state to equitably redistribute resources. According to the PEW Centre[1] most of the respondents from 27 countries believe that elections bring little change, that politicians are corrupt and out of touch and that courts do not treat people fairly. There are many explanations behind the decade long of processes of undoing the march towards democracy.

In Africa the Economist magazine notes the return of military coups as problematic and parks the problem at incumbent regimes, most of which claim to be democratic. These have brought neither prosperity nor security. Real GDP per person in sub-Saharan Africa was lower last year than it had been ten years earlier. The Economists proceeds to argue that more people are dying in small conflicts than at any point since at least 1989. In Nigeria, schools have been abducted. When people lose hope that their lives will improve, they become impatient for change and the risk of coups and civil wars increases sharply.

Maybe the spectacular return of coups has not been adequately understood. There are two sides (nothing new right). What is apparent to all of us is that civilian governments subjected to coups will have failed their citizens somewhat. In this instance these coups are a response to leaders who have personalized government and violated the constitution and made it seem impossible to remove them from office. The coups in this instance are seen as a popular response to authoritarianism. However, the post-coup arrangements do not necessarily point towards the deepening of democracy. In countries such Niger and Burkina the post-coup regimes have reversed trade relations with France especially around natural resources. It is reported for instance that the coup in Niger may have a positive influence on economic development based on new terms of exploiting natural resources.

However, others such as Brian Kagoro, [2]Everisto Benyera and Sabelo Gatsheni, make the connection between the coups of the 1970s into the 1980s with those happening in present day Africa. They argue that the cessation of coups in the later 1990s into the 2000s was not necessarily due to improved conditions of democracy but rather the period coincided with the peak of the unipolar world- dominated by the United States. In this regard the contestations for spheres/territories of influence had dissipated. The resurgence suggests a renewed and frenetic for territorial influence and natural resources. However, it is also true that these coups are not being manufactured and led by foreign intelligence services like in the past.

Another point to be made about this moment is the fact that Africa as a continent has all along been engaged in what has been referred to by others as ‘isophormic mimicry’. This has been explained as a technique in which governments create the outward appearance of highly functioning development institutions to conceal their dysfunction. It has at times been limited to development but there is a growing realization that the institutions to support/enhance democracy face similar challenges. Institutions such as the courts and elections commissions either do not have necessary autonomy or sufficient capacity to enhance democracy. Most of the so-called democracies in Africa are cheap imitations. The main challenge has to do with limited constraints on the Executive branch of government. Usually, an effective judicial system and a strong civil society provide balance to powerful executive branches. But these have been severely eroded over the years. In many African countries, though, rulers allow the opposition to participate in elections but take a thousand precautions to ensure they cannot win, from tampering with the voters’ roll to throttling the media. No fewer than nine African leaders have been in power for more than 20 years. It is hard to expect people to support democracy if all they have experienced is a masquerade of it. In some instances, the preferred term is backsliding of democracy. The causes are usually the same, increasing inequality, an insensitive political elite, populist politics without delivery of public goods and collapse of the development project.

There is an urgent need for conversations and broader mobilization to reset the movement towards inclusive democracy. As noted, the version of democracy that was brought into Africa has been inadequate. Perhaps its biggest weakness is the failure to create a strong connection with the economy beyond the assumptions of market led laissez- faire type of growth, it remains captured by the dominant elite and is subject to manipulation. Furthermore, it has, without intent, led to demobilization of citizens- in many instances the achievement of universal suffrage was viewed as the sine qua none of democracy-yet it should have been as only the beginning. What must we do? In this ten-part blog series I explore ways towards recovery of the democracy project. The main argument is that legislating for multi-party politics and holding regular elections is not enough but probably just the first step. Democracy is a way of public life and not an event. Measuring whether an election is free and fair whilst necessary it also not an adequate measure of democracy. It is a measure of elections. The two are not synonymous. How then do we measure democracy? I make the proposal to apply three related measures to determine the extent to which a country is democratic; (i) the freedoms in the public space (AGORA), (ii) the intensity of citizen-to-citizen engagement in solving public problems and finally the extent to which elections are judged to be free and fair.

Bibliography

- Democracy index 2020 - Economist Intelligence Unit. (n.d.). https://pages.eiu.com/rs/753-RIQ-438/images/democracy-index-2020.pdf

- Wike, R. (2019, April 29). Many across the globe are dissatisfied with how democracy is working. Pew Research Center’s Global Attitudes Project. (https://shorturl.at/cfvC1)

- (2023, May 20). Africa is not broke, Africa is broken | Brian Kagoro. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ifaP5sEVFlA

[1] https://shorturl.at/awC04

[2] Africa Is Not Broke, Africa Is Broken | Brian Kagoro - YouTube

There is talk among many that democracy is under threat, and we are in a period of increasing authoritarianism around the globe. There is widespread evidence of the challenges confronting the prevailing and widely accepted political and governance mechanisms. These include but are not limited to, the attempted coup in the US, increasing intolerance, right-wing nationalism, resurgence of military (popular) coups, and the rise of China. These point towards a major problem in how power is exercised at times for the benefit of a few.

Are these problems pointing towards the collapse of democracy? Our challenge is perhaps we lack conceptual clarity on what we mean by democracy. At the core of democracy is a culture of civility, tolerance, and a commitment to the public space. Over time, however, we have adopted a narrow definition of democracy where it is reduced to the holding of regular elections to decide the new band of officeholders. That is almost like the definition of a republic but not necessarily democracy. Based on this popular but narrow definition we have devoted significant attention to how we hold elections. These are important considerations in any democracy. They ensure that citizens are satisfied and feel that they are represented by the people they choose. Thus, we always argue that ‘elections’ are a necessary but not sufficient condition for democracy. One may ask- what then is outstanding in this equation? Some of us would argue that engaged citizens and the public work that they do are the vital lifeblood of a democracy.

Whilst here let me state that there are three other ways of looking at democracy viz (i) consensus democracy – rule based on consensus rather than traditional majority rule. (ii) Constitutional democracy – governed by a constitution. (iii)Deliberative democracy – in which authentic deliberation, not only voting, is central to legitimate decision-making. In many instances when we talk of democracy, we are referring to constitutional democracy.

In all instances/frameworks of democracy, citizens should be expected to occupy centre stage, again not in that narrow way of delineating who belongs to a country but rather as a distinction with officeholders. Democracy can and should be seen as a centuries-old people’s movement looking at how we can govern ourselves after throwing away the shackles of the monarchy (a symbol of oppression in a particular age). In that regard, democracy is about influencing forms of social organization and collective action to resolve public problems away from what was the preserve of the feudal structures of power. The American and French revolutions played an important role in ushering the democracy under discussion. Tocqueville’s treatise: Democracy in America’ delves deeper into the emerging forms of social organization- especially voluntary associations in that period. This may not look revolutionary today, but it was a novel way of re-organizing society outside of the monarchical feudal relations that existed.

The above definitional argument allows me to proceed to the central argument in this discussion- not all of democracy is under threat but certain aspects of it. The democracy with a small ‘d’ project - the undertakings of citizens (national and transnational) amongst themselves is probably at its peak. Globalisation was initially promoted as an economic project of interdependence. Equally so there is a newly discovered consensus on the need to jointly solve wicked problems. The wicked problems around climate change, the global economic crises, inequality, and poverty are best articulated and resolved in citizen-to-citizen platforms- commonly organized in what we loosely refer to as civil society organizations. Despite concerns to do with unresolved but stark unequal power relations- the global citizen-to-citizen platforms offer us the best possibilities for re-imagining and understanding the strides we have made to sustain democracy. In these spaces we practice (albeit unevenly) values of civil society and mutual respect, we talk about social justice, and accountability, we frown on racism and historical injustices. It is these global mobilizations of ordinary people from various walks of life that should give us hope. These mobilizations have gone through various ebbs and flows- perhaps they were at their peak during the various World Social Forums. People-to-people solidarity. Our democracy is deliberative.

The democracy project with a capital ‘D’ referring to the allocation of power and resources within a country is under threat. At the centre of the threat is the system of free and fair elections requires urgent attention and rethinking. In many instances, these elections produce cliffhanger results and still, the winner must take all with no adequate consideration of the significant minority that didn’t vote for the victorious party or individuals. Take for instance the Democratic Party in the US- they have always won the majority vote in the US since the 1980s and yet they have not necessarily won the right to run the White House due to a very complex process called the electoral college. These challenges are not unique to the US. In many African countries, the ruling political party takes advantage of its incumbency to have a final say over constitutional boundaries. The resolution of the democracy with a capital ‘D’ is within reach thanks largely to the strides that citizens have achieved in establishing various initiatives from the local, national, regional, and global processes. It is these processes that will help shape and define the next phase of the struggle for democracy with a capital ‘D’. There is hope.

In its original formulation democracy was always about direct representation. It originated in the City of Athens (Ancient Greece)- and Cleisthenes also spelled Clisthenes, (born c. 570 BCE—died c. 508) is credited as the founder of modern-day democracy. He successfully allied himself with the popular Assembly against the nobles (508) and imposed democratic reform. Perhaps his most important innovation was the basing of individual political responsibility on the citizenship of a place rather than on membership in a clan. The shift was significant. It led to the thinking of citizens as actors in the public and allowed for the expansion of settlements beyond clan-based systems.

However, even then there were already signs of excluding others. Many philosophers devoted time and thought on what kind of citizen should be part of the public space (the Agora). There were new nuances around wealth and levels of education. Growing populations made it necessary to consider a framework of representation. During the period preceding the industrial age (feudal era), those who did not hold land (known as serfs or peasants) had no public representation. They were subjects of their feudal lords. The lords had ways of representation and engaging with the monarchy, but it was hardly a democracy. For many, modern-day democracy derives its roots from the French Revolution of 1789. The revolution was inspired by ideas of equality of egalitarianism and led to the overthrow of the monarchy in France and in many other places. In its place emerged a new consensus around representative democracy.

Since then, battles have been fought across the globe on the need for universal suffrage. The right to vote for one’s chosen representation. Universal suffrage has been achieved in many parts of the world, but effective representation has not yet been achieved. There are old and new cleavages in society that had either been previously ignored or have recently emerged. However, not all democracies are the same. The achievement of universal suffrage is not an end but may be a great starting point for ensuring adequate representation. One of the assumptions of representation is the idea of voice- the representatives have a voice to speak on behalf of their communities. But as many others have shown not all democracies are the same, according to the Varieties of Democracy project there are four categories of regimes; (i) closed autocracy, (ii) electoral autocracy, (iii)electoral democracy, and (iv) liberal democracy (https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/political-regime?time=2022). These varieties of democracy also point towards uneven levels of representation.

One of the conditions for democracy to work is the need to make sure there is adequate representation in local and central government processes. Differences in society usually manifest through racial, language, demographic, and gender-based groups. In some instances, geography matters. Take for instance the ongoing public fight within Zimbabwe’s largest opposition party around recalls. It seems one of the major complaints amongst those doing the recalling of Members of Parliament is the challenge they face in being represented by people who do not originate from the same area and are also not of the same language group. In a polarized environment, these concerns have been reduced to ‘tribalism.’ At the centre of democracy is the idea that everyone’s voice must be heard. The responsibility and processes of choosing a representative cannot be subcontracted to a party’s leadership. The communities must feel that they have a stake in the process and should have confidence in the process. Anything lesser than this golden standard will lead to alienation from the public space and frustration.

The achievement of adequate representation also requires consideration of groups that have been historically excluded from holding public office. The historically excluded include women, youth, language/tribal minorities, and special interest groups (such as people living with disability). Several African governments have come up with quota systems for public offices to ensure improved participation of women, youths, and in some instances, people living with disabilities. Several constitutions written in the 1990s and 2000s have made significant progress in ensuring that there is adequate representation.

However, there are ongoing concerns that some governments have been undoing some of these provisions. Perhaps the real challenge has nothing to do with legislation, but the focus must instead shift towards practices within political parties vying for office. How have these entities established norms and frameworks to enhance adequate representation within political party processes and in the selection of their leaders? Political parties, just like governments face the real risk of isomorphic mimicry- where they may seem (to outsiders) as democratic when in fact there is a single leader or a cabal of established elites making all the decisions. There is a need for a thorough examination of the different social and demographic groups/interests within the party and the extent to which they are represented. Diversity is beautiful but it can lead to fragmentation if the different groups are not adequately represented. Adequate representation not only in terms of holding office but in the day-to-day decision-making processes should the North Star of a political party pursuing public office. Otherwise, what is the guarantee that they will be democracy after winning the elections?

There is another dimension to representation- the need to make sure all public problems/ issues are given adequate consideration. Communities are not the same-they face different and at times unique challenges. There is always an assumption that representation by area resolves challenges to do with uneven development. In many instances, representatives can be marginalized especially in the absence of an evidence-driven policy-making culture. Representation requires effective bottom-up participation (see next post)

Democracy depends on increasing the voice of local communities, respecting the rule of law, promoting equity and justice, and the participation of the beneficiary communities in decision-making. Broad participation has been identified as a potential antidote to the unfettered expansion of expert-based approaches that exclude citizens. Effective participation depends on the recognition and affirmation of the right to engage. In many instances, we loosely refer to those who are able or aspire to effectively participate in public problems as citizens. For this blog series, I consider a citizen as one who shares in governing and being governed in the best state, he/she is the best able one and chooses to be governed and govern with a view to the life of excellence (adapted from Everson 1988- see also Murisa, 2020). Traditionally citizenship has been viewed as relating to belonging to a state and enjoying its rights while simultaneously fulfilling obligations required by that state (Turner,1997; Masunungure and Koga, 2013). In this discussion, I focus on citizenship as a verb entailing the actions taken by citizens individually and collectively to improve the public space. Citizenship is the bedrock against which individuals can claim services from their government or seek to participate in national processes, including for or being voted into office (Masunungure and Koga, 2013).

The Zimbabwean Constitution affirms broad-based participation in national processes as an indivisible right. Section 13 (2) of the constitution obligates the Government to

"…involve the people in the formulation and implementation of development plans and programs that affect them". Citizens acknowledge the need for their engagement with officeholders but indicate facing multi-layered challenges in seeking that engagement (International Republican Institute 2015, Ndoma and Kokera, 2016).

As individuals become more acquainted with the democratic process they gain more confidence, which makes them more effective advocates for reforms to specific policies.

Typically, citizens participate in the public space in different ways, including engaging in forms of solidarity towards one another, protesting unjust/unfair decisions, coproduction with formal organizations, and political decision-making (voting). The most common or popular forms of civic participation have been through public protests (see Murisa, 2022: 94-109). Yet there are several instances of other effective citizen-led/inspired participation. Zimbabwe has normative frameworks for citizen participation for the individual to influence practices and policies both at local and central government levels. These include budget consultations, participating in local government elections, being a part of consultative forums, public hearings, councils' open meetings, the Village Development Committee (VIDCO), Ward Development Committee, Rural District Development Committee, and Provincial Development Committee (Chikerema, 2013:88-89).

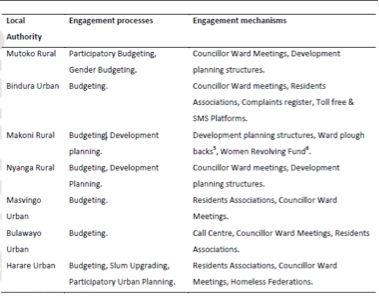

Figure 2: Citizen engagement processes and mechanisms Source: Muchadenyika, 2017

However, effective citizenship or participation does not happen by itself. Citizens may feel powerless or do not see the need to exercise control of their communities and national future. Furthermore, effective citizenship may be constrained when officeholders within government and formal non-state organizations create the 'impression' of participation when the end goal has already been established. Several formalized organizations working within the civil society space have carved a niche as an alternative to an ineffective and corrupt state and a rapacious business sector and have positioned themselves as the unelected and un-legitimized voice of the citizens. They have not necessarily invested in developing the voices of the poor and bonds of trust that can be used to unleash community participation in local and national processes outside of the framework of the scope of a defined project. Participation of citizens is an ideal that many official processes have failed to achieve and instead, they have created 'invited' spaces which in effect serve to constrain rather than unleash the civic capacities of citizens. Participation theorists such as Cornwall (2008), Gaventa (1993, 2005), and Chambers (1983) have contributed important insights to the dilemmas of effective participation. Eversole (2010:37) captures this dilemma in a very precise way when she observes that:

…the problem of participation is not that participation is impossible to achieve; but rather, that it is impossible to achieve for others… Rather, the challenge of participation is about how to become participants in our rights: choosing to move across institutional and knowledge terrains to create new spaces for communities and organizations to 'participate' together.

Many existing initiatives of participation are characterised by 'invited' spaces and managed projects instead of what Cornwall (2008) terms spaces that people create for themselves. Gaventa (2005) weighs in by suggesting that for there to be effective participation there is a need to work on participation from both sides of the equation: that is, to increase both the participation of communities and the responsiveness of government institutions. The challenge for Zimbabwe and indeed other emerging democracies is to remake participation through the reframing of interactions amongst communities, professionals, and institutions into a truly participatory space. A supply of good institutions and organizations is not enough. To create them by legislative edict does not make them work. Somehow people must be empowered to insist on good governance according to their terms. But wanting it does not make it happen. Institutions will work when a public covenant builds around them and demands that they work. A civic compact between formally established organizations and communities is what makes it sustainable, and it should begin at the level of communities. Only then can it be usefully facilitated by the well-placed civic investments of philanthropic donors. Civic values must emerge organically from the public life of communities.

Bibliography:

Aristotle. (trans. 1932). Politics (H. Rackham, Trans.). Harvard University Press

Chambers, R. (1983). Rural development: Putting the last first. Longman.

Chikerema, A. F. (2013). Citizen participation and local democracy in Zimbabwean local government system. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 3(11), 88-99.

Cornwall, A. (2008). Unpacking 'participation': models, meanings, and practices. Community Development Journal, 43(3), 269-2831

Gaventa, J. (1993). The powerful, the powerless, and the experts: Knowledge struggles in an information age. In P. Park, M. Brydon-Miller, B. Hall, & T. Jackson (Eds.), Voices of change: Participatory research in the United States and Canada (pp. 21-40). Bergin & Garvey.

Muchadenyika, D. (2017). Citizen engagement processes and mechanisms. In R. M. Chakaipa & S. Mudimu (Eds.), Local government reform in Zimbabwe: A policy dialogue (pp. 133-152). African Books Collective

Murisa, T. (2020) Whose Development: Examining the Extent to Which Development Actors Align with Communities.

Murisa, T. (2022). Rethinking Citizens and Democracy. SIVIO Publishing. Harare.

Ndoma, J., & Kokera, H. (2016). The role of the international observer in the consolidation of democracy in Nigeria: A case of 2015 general elections. European Journal of Political Science Studies, 4(3), 34-80. Retrieved from EJPS website.

Turner, B. S., Masunungure, E. V., & Koga, H. (2013). Citizenship in Africa: The politics of belonging. Africa Development, 38(3), 1-18.-18.

Political systems have evolved over time. Thomas Hobbes (1651) argued that within each of us lies a representation of general humanity and that all acts are ultimately self-serving. He suggested that in a state of nature, humans would behave entirely selfishly. He concludes that humanity's natural condition is a state of perpetual war, fear, and amorality and that only government can hold a society together. He argued for the necessity and natural evolution of the social contract, a social construct in which individuals mutually unite into political societies, agreeing to abide by common rules and accept resultant duties to protect themselves and one another from whatever might come otherwise. His proposal however was not for a democratic order as we know it today instead, he proposed a strong central government, one with the power of the biblical Leviathan (a sea creature), which would protect people from their selfishness. Even though his prescription was not for a democratic order as we know it today, he acknowledged the need for cooperation within political societies.

However, Paleo-political anthropology studies [1] have demonstrated that, long before kingdoms and nation-states were established, our ancestors had found ways to cooperate for human survival whether as hunter-gatherers or as settled agriculturalists. It is these forms of cooperation that precede Greek philosophers who are said to have discovered democracy (see Mathews,). Fukuyama [2] writes; "Human beings never existed in a pre-social state. The idea that human beings at one time existed as isolated individuals, who interacted either through anarchic violence (Hobbes) or in pacific ignorance of one another (Rousseau), is not correct". Democracy is a social rather than a political term to refer to a society marked by equality of social conditions with no ascriptive aristocracy, and all careers open to all citizens including the opportunities to be in government (Tocqueville 1835). The kind of democracy under discussion is the one that assumes that no one of us will make the best decision for others-we have to figure it out for ourselves. In other words, democracy is about learning together.

Democracy is based on balancing power, making trade-offs, and ensuring civil liberties, and more importantly, it is about making sure that citizens are engaged in solving problems. These roles cannot be dispensed by an invested political elite alone, there is a need for broadening our understanding of how democracy works. Besides, not all the change needs to happen within government or led by government but most of the work of democracy is the work of citizens. The challenge in Zimbabwe and indeed in many other countries is that the idea of citizens is restricted mostly to voting and, in many cases, they are mostly referred to as voters. Voting is a necessary function within our democracy, but it is also not the only function of citizens. In other instances, citizens have been equated to the work done by non-state actor institutions such as NGOs, human rights groups, unions, etc. Non-state actor institutions are at a preliminary level indeed an expression of citizens' interest but over time a disconnect can also occur in which citizen interests remain at the periphery of what these institutions do.

There is a need for the emergence of a civic agency that is built through ongoing collective work where citizens begin to see themselves as co-creators of a new democratic governance framework. First, we must get beyond an overreliance on experts and begin to tap into various forms of knowledge embedded within communities. Boyte (2009:3) argues that 'we have to get beyond expert cults if we want to develop civic agency, the capacities of people and communities to solve problems and to generate cultures that sustain such agency'. David Mathews (2020), writing in a context of warning trust in the representative state system suggests that maybe this could be the time to reconsider Abraham Lincoln's ideal of a government of, by, and for the people in the Gettysburg Address to include governing with the people. According to Mathews a 'with' strategy encourages collaboration through mutually beneficial or reinforcing efforts between the citizenry and the government. It fosters collective work, not only among people who are alike or who like one another but among those who recognize they need one another to survive or to live the lives they want to live. In his formulation of the 'with' strategy, in which he describes complementary production fostering reciprocity between what citizens do and what governments do. The strategy is based on evidence that governments at any level can't do their jobs as effectively without the complementary efforts of people working with people.[1] That is because some things can only be done by citizens or that are best done by them. People aren't the only ones who need people democratic governments need working citizens. An instance of citizens' complementary production does not necessarily need to be organised through the state, but they produce public goods such as welfare, public safety, and food security which are otherwise traditionally provided for by the state.

Second, there is a need to make sure that there are adequate platforms for expression. Communities are unique. Individuals within different communities will build their civic agency based on the needs/challenges that they are responding to. There is a need to avoid prescriptive frameworks. Third, evidence from many studies has shown that individuals who are members of associations tend to be more interested in politics, better informed and to be more often involved in acts of political participation than people who are not members of such associations. Civic activism impacts the public arena positively because associations support the social infrastructure of public spheres that develop agendas, test ideas, embody deliberations, and provide voice. In almost every community (rural and urban) there is a mosaic of associational forms that includes loose unstructured networks such as civic engagement associations, residents' associations, neighbourhood watch committees, faith-based associations, loans, and savings associations, women's associations, burial societies, and professional associations are active across the length and breadth of Zimbabwe. These are the incubators of cooperation and democracy.

The associative activities take the form of popular local organisations, and their proliferation is based on the real needs, interests, and knowledge of the people involved. These flourish in any environment, even in areas that do not encourage independent association. There is a wide range of associational forms in both the rural and urban settings, including savings and loans societies, self-help organisations, multi-purpose cooperatives, occupational groupings, farmers unions, and, since the 1960s, rural-based NGOs. The leadership in these associations originates from amongst the concerned communities. Tocqueville (1840) notes that associations are the key features of democracy. When Alexis de Tocqueville visited the United States in 1832 he was struck by the vitality of its civic sphere: "Americans of all ages, all conditions, all minds constantly unite…". Tocqueville identified four different roles of associations as per the Table below:

Table 1-1 The Role of Associations

|

Role |

Descriptions |

|

Integrating |

They provide citizens an opportunity to develop norms of enlightened self-interest and the skills and habits of cooperation. The method of integration is horizontal working through social networks among equals rather than relationships of dependency |

|

Differentiating |

They provide space for individuals to form associations with distinct interests and identities. Provide a sense of community even for those who hold beliefs that are not accepted by the majority-mediating the tyranny of the majority opinion |

|

Capacity Building |

Citizens learn the skills and habits of collective action and organize themselves to accomplish great deeds |

|

Synergistic |

Reciprocal actions of man upon one another. Citizens in a democracy can exert social and political power rather than relying upon the power of great individuals. |

How can these formations contribute towards deepening the process of democracy? Very little has been invested in terms of working with these associations as part of a broader engagement on national and local democracy. Tocqueville's asserted that 'in democratic countries, the science of association is the mother of science'. However, although writing about a different context, John McKnight (2013:7) observes that 'no university has yet created a Department of Associational Science'. The Zimbabwean situation is very close to what is prevailing in other regions. In most instances, these voluntary associational forms do not feature within the democratization discourse, especially around big projects such as constitutional reform and elections. The potential synergy that can be derived through engaging local formations is underestimated especially within the realm of politics in government and civil society. They provide a platform for broad-based mass mobilization as we have seen in Latin America within the land movements and in former communist countries such as Poland where engaged citizens gathered under the banner of 'Solidarity' toppled a dictatorship. However, most analyses of the public space have unfortunately been devoted to the professionalized spaces dominated by donor-supported NGOs. These NGOs and other professionalized formations are not necessarily at the center of organic community mobilization and in many cases their consultative and consensus-building capacity is inadequate.

Following the pattern established by Ostrom and Gardener (1993:7) we propose to consider the different forms of cooperation that citizens forge with each other on an everyday basis and using Briggs' formulation consider this cooperation as part of problem-solving which contributes significantly to the texture of a democracy. We note that citizens and the formations they establish assume different roles ranging from cooperating with one another to strengthening prospects for economic survival/competitiveness, giving to each other, and confronting power.

Bibliography:

Barker, E. (2011). The role of associations. In J. Scott & P. Carrington (Eds.), The SAGE Handbook of social network analysis (pp. 196-214). SAGE Publications1

Boyte, H. C. (2009). Civic agency and the cult of the expert. Kettering Foundation1

Fukuyama, F. (2011). The origins of political order: From prehuman times to the French Revolution. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Hobbes, T. (1996). Leviathan (R. Tuck, Ed.). Cambridge University Press. (Original work published 1651) 1

Mathews, D. (1997). Politics for people: Finding a responsible public voice. University of Illinois Press

Mathews, D. (2020). With the people: An introduction to an idea. Kettering Foundation Press1

McKnight, J. (2013). The abundant community: Awakening the power of families and neighbourhoods. Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Ostrom, E. (1993). Covenanting, co-producing, and the good society. PEGS Newsletter, 3(2), 8.

Tocqueville, A. de. (2000). Democracy in America (H. C. Mansfield & D. Winthrop, Trans.). University of Chicago Press. (Original work published 1835) 1

Tocqueville, A. de. (2000). Democracy in America (H. C. Mansfield & D. Winthrop, Trans.). University of Chicago Press. (Original work published 1840) 1

The question of whether democracy has a direct relationship with the pursuit of inclusive economic development has been asked several times. Let us start with a quote from Venezuela's former President -Caldera.

It is difficult to ask the people to sacrifice themselves for freedom and democracy when they think that freedom and democracy are incapable of giving them food to eat, preventing the astronomical rise in the cost of subsistence, or placing a definitive end to the terrible scourge of corruption that, in the eyes of the entire world, is eating away at the institutions of Venezuela with each passing day.

As already stated, (see Introductory blog) democracy is in recession. According to Freedom House, democracy has been in recession for the past 15 years globally—a bit concerning for many of us. There are concerns with the resurgence of coups across Africa, rising intolerance of diversity and dissent, and exclusive nationalism. In many parts of Africa, election results are routinely challenged as not reflecting the will of the majority. Reports of arrests and torture of human rights defenders and governance activists have become part of daily reporting.

What shall we do? First things first- what if we are not naming the problem adequately? Yes, it is a problem of democracy- the constitutional type (see A Difficult Moment for Democracy, There Is Hope Part 2). However, the convulsions that we are seeing have to do with consumption and accumulation patterns. There are protests here and there about the failure to conduct elections properly. However, most of the protests that we mapped (https://africacitizenshipindex.org) have to do with poverty, jobs, corruption, police brutality, and rarely about elections or broad democracy. Are these issues unrelated to democracy? Perhaps, instead of focusing on increasing authoritarianism- what if we asked ourselves, ‘What else is happening in these countries where democracy is failing?

Could it be that they are the same countries associated with weak to non-existent economic growth? Everyday citizens rarely come out to say we are defending democracy (except maybe in America after the threats on Capitol Hill). In many instances, citizens come out to protest over the failings of the economy and specifically name the problems ranging from lack of jobs, increasing cost of living, lack of access to affordable health care, security, etc. On the face of it all these are problems of the economy and not necessarily the political system in place.

Could it be that democracy has been let down by the economic framework- especially the free market economy? Many countries that are going through various types of economic crises- have also found themselves confronting governance challenges that spring from how governments respond to citizen mobilisation (protests) or the realisation on the part of ruling elites that they may lose an election due to the failings in the economy. What then shall we fix, democracy or the economy? Others may say both. For many of us in Africa we have been seized with the infrastructure of democracy, developing, and adopting new constitutions, ensuring separation of powers, establishing independent commissions, and developing frameworks for the achievement of civil and political freedoms. Admittedly the process has been uneven, but we have made progress. At some point, the continent had managed to ‘silence the guns’ in terms of eradicating or reducing incidences of armed civil conflict and to agree on a consensus against coups. There is a strong democracy-oriented infrastructure within the African Union (AU).

However, challenges persist. Could it be that we have not paid sufficient attention to the attendant existing weakness within the economy? It is important to state that democracy has always been promoted together with a free market economic model. Most African countries conducted thoroughgoing economic reforms to align with free market thinking. Things got worse. Many jobs were lost in the civil service- it was argued that African governments had bloated bureaucracies- so they carried massive retrenchments and, in the process, rendered these bureaucracies ineffective. The small delicate steps towards industrialisation were crashed due to the insistence for liberalisation of trade and removal of tariffs. Retrenchments and company closures were the order of the day. For some reason, the same period was also associated with the growth of rapacious greed and corruption on the part of the political class. They moved from one scandal to the next- literally emptying state coffers and selling off strategic assets to ‘investors’ at rock bottom prices as part of the privatisation drive. The three decades of the free market have been nothing but disastrous for many. The benefits from the cited economic growth have not been widely shared. Instead, there are new Yachts and private planes owned by the elite thinly spread across the continent with properties in Dubai and offshore bank accounts. The middle class (driver of growth) has been thoroughly destroyed.

There was a brief hiatus- when China was growing at a breakneck speed. Many African countries benefited (in a limited way) due to China’s huge appetite for natural resources and agricultural products from Africa. However, China has since put brakes on its growth trajectory. Commodity prices have collapsed once again, and we are in an unprecedented economic crisis that is not only multifaceted but is taking place alongside and within the global economic crisis. The protests and civil unrests are back including military coups. Could this be an inflection point for both the economy and democracy here in Africa?

What shall we do?

Fixing democracy requires us to acknowledge its umbilical cord-like relationship with the economy. It is also an egg and chicken relationship-there is no clarity on which one should happen first. Others say fix democracy and the rest will sort itself. We have tried that and yet both are in disarray. Maybe let’s focus on simultaneously fixing both. Note that I am using ‘we’ and ‘us’ because I don’t believe this a project that can be handed over to governing and connected business elites. Citizens need to be engaged in the same way as we have been in the struggle for democracy.

There is an urgent need to rethink the characteristics of the economic model that will work. A foreign direct investment model will not work. African economies are required to urgently integrate value chains. Many countries depend on the export of primary commodities with no value addition despite the various studies that have demonstrated that this has ensured our continued impoverishment. Our agitations should be for the establishment of industrialisation and innovation funds that are managed transparently. In the interim, governments need to come up with a more effective taxation system. Africa continues to lose over $20 billion annually through illicit financial flows. In many instances what is derogatorily referred to as the 'informal sector’ is the equivalent of the cottage industry in other countries except that in many African countries players in this sector have never received an incentive from their governments. Yet the same sector has the potential to be the largest employer in countries beset by low levels of industrialisation. However, we continue to shun it and keep it out of formal financial circuits. There are many other low-hanging fruits and long-term suggestions for fixing the economy.

There is an urgent need for working economies that can address issues to do with increasing unemployment, inflation (erosion of incomes), weak social service delivery, and unjust patterns of economic extraction and accumulation. The alternative is too ghastly to contemplate but can be summarised in one word- COLLAPSE. We cannot fix democracy when the economy is in disarray.

According to Freedom House democracy has been in recession for the past 15 years globally. A bit concerning for many of us. Admittedly democracy is not necessarily the ideal framework of governance, but it is the best we have to date. There are concerns to do with the resurgence of coups across Africa, rising intolerance of diversity and of dissent and exclusive nationalism. In many parts of Africa election results are routinely challenged as not reflecting the will of the majority. Reports of arrests and torture of human rights defenders and governance activists has become part of daily reporting.

What shall we do? First things first- what if we are not naming the problem adequately? Yes, it is a problem of democracy- the constitutional type (see Part 1). However, the convulsions that we are seeing have to do with consumption and accumulation patterns. There are protests there and there about the failure to run elections properly. However, most of the protest that we mapped (https://africacitizenshipindex.org) have to do with poverty, jobs, corruption, policy brutality and rarely about elections or broadly democracy. Are these issues unrelated to democracy. Perhaps, instead of focusing on increasing authoritarianism- what if we asked ourselves, ‘what else is happening in these countries where democracy is failing?

Could it be that they are the same countries associated with weak to non-existent economic growth? Everyday citizens rarely come out to say we are defending democracy (except maybe in America after the threats on Capitol Hill). In many instances citizens come out in protest over the failings of the economy and specifically name the problems ranging from lack of jobs, increasing cost of living, lack of access to affordable health care, their security etc. On the face of it all these are problems of the economy and not necessarily the political system in place.

Could it be that democracy has been let down by the economic framework- especially the free market economy. Many countries that are going through various types of economic crises- have also found themselves confronting governance challenges that spring from how governments respond to citizens mobilization (protests) or realization on the part of ruling elites that they may lose an election due to the failings in the economy. What then shall we fix, democracy or the economy? Others may say both. For many of us in Africa we have been seized with the infrastructure of democracy, developing, and adopting new constitutions, ensuring separation of powers, establishing independent commissions, developing frameworks for the achievement of civil and political freedoms. Admittedly the process has been uneven, but we have made progress. At some point the continent had managed to ‘silence the guns’ in terms of eradicating or reducing incidences of armed civil conflict and to agree on a consensus against coups. There is strong democracy-oriented infrastructure within the African Union (AU).

However, challenges persist. Could it be that we have not paid sufficient attention to the attendant existing weakness within the economy. It is important to state that democracy has always been promoted together with a free market economic model. Most African countries carried out thoroughgoing economic reforms to align with free market thinking. Things got worse. Many jobs were lost in the civil service- it was argued that African governments had bloated bureaucracies- so they carried massive retrenchments and, in the process, rendering these bureaucracies ineffective. The small delicate steps towards industrialization were crashed due to the insistence for liberalization of trade and removal of tariffs. Retrenchments and company closures were the order of the day. For some reason the same period was also associated with the growth of rapacious greed and corruption on the part of the political class. They moved from one scandal to the next- literally emptying state coffers and selling off strategic assets to ‘investors’ at rock bottom prices as part of the privatisation drive. The three decades of the free market have been nothing but disastrous for many. The benefits from the cited economic growth have not been widely shared. Instead, there is a new Yacht and private planes owning elite thinly spread across the continent with properties in Dubai and offshore bank accounts. The middle class (driver of growth) has been thoroughly destroyed.

There was a brief hiatus- when China was growing at a breakneck speed. Many African countries benefited (in a limited way) due to China’s huge appetite for natural resources and agricultural products from Africa. However, China has since put brakes on its growth trajectory. Commodity prices have collapsed once again. And we are in an unprecedented economic crisis that is not only multifaceted but is taking place alongside and within the global economic crisis. The protests and civil unrests are back including military coups. Could this be an inflection point for both the economy and democracy here in Africa?

What shall we do?

Fixing democracy requires us to acknowledge its umbilical cord like relationship with the economy. It is also an egg and chicken relationship-there is no clarity on which one should happen first. Others say fix democracy and the rest will sort itself. We have tried that and yet both are in disarray. Maybe let’s focus on simultaneously fixing both. Note that I am using ‘we’ and ‘us’ because I don’t believe this a project that can be handed over to governing and connected business elites. Citizens need to be engaged in the same as we have been in the struggle for democracy.

There is an urgent need for a rethink on the characteristics of the economic model that will work. A foreign direct investment model will not work. African economies require to urgently integrate value chains. Many countries depend on the export of primary commodities with no value addition despite the various studies that have demonstrated that this has ensured our continued impoverishment. Our agitations should be for the establishment of industrialization and innovation funds that are managed transparently. In the interim governments need to come up with a more effective taxation system. Africa continues to lose over $20Billion annually through illicit financial flows. In many instances what is derogatorily referred to as the ‘informal sector’ is the equivalent of the cottage industry in other countries except that in many African countries players in this sector have never received an incentive from their governments. Yet the same sector has potential to be the largest employer countries beset by low levels of industrialization. However, we continue to shun it and keep it out of formal financial circuits. There are many other low hanging fruits and long-term suggestions for fixing the economy.

There is an urgent need for working economies that can address issues to do with increasing unemployment, inflation (erosion of incomes), weak social service delivery, and unjust patterns of economic extraction and accumulation. The alternative is too ghastly to contemplate but can summarized in one word- COLLAPSE. We cannot fix democracy when the economy is in disarray.

There is talk among many that democracy is under threat, and we are in a period of increasing authoritarianism around the globe. There is widespread evidence of the challenges confronting the prevailing and widely accepted political and governance mechanisms. These include but are not limited to, the attempted coup in the US, increasing intolerance, right wing nationalism, resurgence of military (popular) coups and the rise of China and unending concerns about the abuse of power especially in Africa. These point towards a major existential problem for democracy.

Are these problems pointing towards the collapse of democracy? There is need for conceptual clarity on what we mean by democracy. At the core of democracy is a culture (way of life) of civility, tolerance, and a commitment to the public space. Whilst here let me state that there are three ways of looking at democracy and viz (i) consensus democracy — rule based on consensus rather than traditional majority rule. (ii) Constitutional democracy — governed by a constitution. (iii)Deliberative democracy — in which authentic deliberation, not only voting, is central to legitimate decision making. In many instances when we talk of democracy, we are referring to constitutional democracy.

Over time however we have adopted a narrow definition of democracy where it is reduced to the holding of regular elections to decide on the new band of officeholders. That is almost like the definition of a republic but not necessarily democracy. Based on this popular but narrow definition we have devoted significant attention to how we hold elections. These are important considerations in any democracy. They ensure that citizens are satisfied and feel that they are represented by people they themselves chose. But that is not enough. Thus, we always argue that ‘elections’ are a necessary but not sufficient condition for democracy. One may ask- what then is outstanding in this equation? Some of us would argue that engaged citizens and the public complementary work that they do are the vital lifeblood of a democracy.

In all frameworks of democracy citizens are expected to occupy centre stage, again not in that narrow way of delineating who belongs to a particular country but rather as a clear distinction with officeholders. These need to be engaged citizens- who regularly makes efforts to work alongside others in collectively resolving public problems. Democracy can and should be seen as a centuries old people’s movement that is looking at how we can govern ourselves after throwing away the shackles of monarchy (a symbol of oppression in a particular age). In this regard democracy is about constantly re-imagining shifting our forms of social organisation and collective action to resolve public problems away from what was the preserve of the feudal structures of power. The American and French revolutions played an important role in ushering the democracy under discussion. Tocqueville’s treatise: Democracy in America’ delves deeper into the emerging forms of social organisation- especially the voluntary associations that he observed spread across America in that period. This may not look revolutionary today, but it was a novel way of re-organizing society outside of the monarchical feudal relations that existed and as part of the vast undertaking of building a nation.

The above definitional argument allows me to proceed to the central argument in this discussion- not all of democracy is under threat but certain aspects of it. The democracy with a small ‘d’ project — the undertakings of citizens (national and transnational) amongst themselves is health and probably at its peak. Globalisation was initially promoted as an economic project of interdependence. Equally so there is a newly discovered consensus on the need to jointly solve wicked problems at a transnational scale. Today, the wicked problems around climate change, the global economic crises, inequality, and poverty are best articulated and resolved in citizen-to-citizen platforms- commonly organized in what we loosely refer to as civil society organisations (covering advocacy organisations, membership-based associations, unions of farmers, social movements etc). Despite concerns to do with unresolved but stark unequal power relations in these space- the global citizen to citizen platforms offer us the best possibilities of re-imagining and understanding the strides we have made to sustain democracy. In these spaces we practice (albeit unevenly) values of civil society, mutual respect, we talk about social justice, accountability, we frown on racism and historical injustices. It is these global mobilizations of ordinary people from various walks of like that should give us hope. These mobilizations have gone through various ebbs and flows- perhaps they were at their peak during the various World Social Forums. People to people solidarity. Our democracy is deliberative.

The democracy project with a capital ‘D’ referring to the allocation of power and resources within a country is under threat. At the centre of the threat is the system of free and fair elections. This requires urgent attention and rethinking. In many instances these elections produce cliffhanger results and still the winner must take all- with no adequate consideration of the significant minority that didn’t vote for the victorious party or individuals. Take for instance the Democratic Party in the US- they have always won the majority vote in the US since the 1990s and yet they have not necessarily won the right to run the White House due to a very complex process called the electoral college. These challenges are not unique to the US. In many African countries the ruling political party takes advantage of its incumbency to have a final say over constitutional boundaries. The resolution of the democracy with a capital ‘D’ is within reach thanks largely to the strides that citizens have achieved in establishing various initiatives from the local, national, regional, and global processes. It is these processes that will help shape and define the next phase of the struggle for democracy with a capital ‘D’. There is hope.

Zimbabwe: Time to Re- Imagine a New Framework for Democracy

Zimbabwe has just gone through another round of harmonized elections. The outcomes were predictable from the beginning. A contested win for the ruling ZANU-PF. The opposition didn’t do so badly. They won in all major cities and towns. They also increased their representation in Parliament. The opposition has not contested any of the ward or parliamentary results. They have dismissed the presidential election results as not reflecting the will of the people. They have cited (and reasonably so) attempts at voter suppression and frustration in both Harare and Bulawayo, strongholds of the opposition. They are not alone. For the first time the SADC Elections Observer Mission wrote a somewhat scathing report about the conduct of elections. Unfortunately, the current version is limited to the conduct and not the tallying of vote numbers. Prior to the actual voting the leader of the opposition had assured voters that they have put in place an anti-rigging mechanism.

There are several others within the opposition and in broader civil society that are engaged in efforts to have the vote annulled based on the claims of rigging. The online petition seems to be gaining ground. The call for annulment if successful would be a great victory for opposition forces. However, it is highly unlikely that this will happen. Perhaps it’s time to look ahead and think through what can be done differently in the future.

For some of us democracy is not necessarily about elections. We agree that elections are a necessary but not sufficient condition for democracy. The whole democracy apparatus depends on active citizenship. Probably one of the biggest mistakes made in the last two decades has been to reduce citizens into voters. Just look at the millions of dollars poured into voter education campaigns. To what end? To get the vote out. However, this is potentially the weakest form of democracy- where all you need from citizens is their vote.

The retreat from citizenship to voters has taken place over a long time. Let’s look at events of the last two decades or so.

The waning of ZANU-PF’s popularity especially during structural adjustments days led to the congealing of new coalitions of struggle initially for social Justice and later towards to governance issues. Here is a rough schematic of what was proposed as solutions. They all liked silver bullet like solutions-

First: it was proposed that there is need for a new constitution which will fix our problems- so the citizens were told and believed. They actively participated in rejecting the ZANU-PF’s version of the constitution. In hindsight if we had accepted that constitution Mugabe would have retired after two terms (circa 2010). We eventually got a new ‘democratic’ constitution in 2013.

Second- we soon realized the need for a new political party- citizens were told and believed. No one has ever come back to them to explain the numerous splits and the harm they cause.