Originally posted on Kettering Foundation: https://kettering.org/africas-gen-z-democracys-last-line-of-defense/

The African continent has 400 million youths aged 15–35 years, and they are playing a major role in determining the pulse of democracy. Young people are the largest voting cohort in Africa. In South Africa, they constitute 42% of registered voters and are 62% of the voting population in Ghana. They have driven major protests, including the most recent one in Kenya. However, they have also supported coups in Niger, Burkina Faso, and Zimbabwe and have been at the center of popular uprisings that have yielded to military-led transitions in Egypt and Sudan. African youths prefer democracy to authoritarianism, but they are more likely than their elders to be dissatisfied with the way democracy is currently working in their countries. The danger is that if the aspirations of youth are not addressed via democratic processes, their dissatisfaction with the establishment may give way to support for authoritarian alternatives.

From Winds of Change to Autocratization

The coups pose a significant threat to the ongoing process of democratization that Africa earnestly began in the 1990s. During this time, the Wind of Change brought a legal shift from one-party states into constitutional multiparty democracies. A new compact against military coups was also formed. The African Union and the Economic Community of West African States adopted a resolution to not accept governments that emerged out of military-led establishments. The consensus lasted for at least a decade. Since the early 2000s, evidence is also pointing toward reversing these democratic transitions to non-democratic regimes in a third wave of autocratization.

Despite the role that young people have played in supporting recent military coups, there is excitement about the potential of a Gen Z-driven democratic consolidation across Africa. The Afrobarometer report also notes that late millennials and Generation Z have broadened their political behaviors beyond voting to embracing collective action to advance new democratic ideals. But the same youth have a greater willingness to tolerate military intervention when elected leaders abuse power. They are also less trustful of government institutions and leaders. Furthermore, the findings from the Afrobarometer survey may suggest youth attitudes toward democracy are contradictory, but they may also point toward flexibility in dealing with existing contexts. The youths are probably more interested in the performance of political regimes than the rhetoric of democracy. The Kenyan youth have been actively demonstrating against specific government policies. The public role of African youth has mostly entailed protesting (at times violently) against economic injustices, corruption, police brutality, governance, and election-related concerns.

- Since the Arab Spring, youth movements have helped remove long-term authoritarian regimes in Tunisia, Egypt, Sudan, and Zimbabwe. However, their role in Zimbabwe is somewhat disputed given the central role of the military in orchestrating the change of government.

- In Malawi, the youth played a central role in disputing what was perceived as a rigged outcome of the 2018 elections. The attention led to the nullification of the results and new elections.

- In Senegal, youths successfully protested former President Macky Sall’s decision to imprison opposition political leaders and postpone the elections. A number of youth leaders that had been arrested were then released, and the election postponement was ruled illegal.

- In Ghana, Nigeria, and South Africa, the youths have protested the unaffordable costs for tertiary education (#feesmustfall), police brutality (#endsarsnow), economic crisis, and rising youth unemployment. The abuse of international debt has been publicly rallied against in Ghana and Zambia.

These protests are not one-off events. In some countries—Ghana, Nigeria, Uganda, and South Africa—it has become normal to witness at least four protests a month. The specific grievance or rallying point may shift, but the root problems are always the economy, the increasing cost of living, and governance blunders.

In 2024, the Kenyan #RejectFinanceBill2024 protests have not only animated the African public space but also inspired movements beyond the continent. The Gen Zs of Kenya (a seemingly leaderless movement) successfully protested the imposition of a new tax that the government intended to use toward settling international debt. The original draft of the bill would have increased levies on basic daily needs such as fuel, mobile money transfers, internet banking, sanitary pads, and diapers.

These protests suggest a broadened understanding of democracy beyond elections. From the youths’ perspective, democratic governments should be able to resolve economic and social injustices. They are focused on reforming not only the national but also international political and economic frameworks. At the national level, they have sought to expose and, where possible, remove a corrupt and illegitimate government. At the international level, the Gen Zs have devoted their energies to challenging remnants of colonial power, especially in Francophone Africa and the international financial system. In Senegal, Burkina Faso, and Mali, there has been a consensus to challenge French hegemony in the affairs of former colonies. The youth vote in Senegal was in many ways an expression of their discontent with how the French continued to exercise power, especially around economic reforms and fiscal policy. Rallies in Kenya have been largely against President William Ruto, but protesters are also speaking out against the IMF. Gen Z protesters throughout the African continent are focused on the wasteful local elite and on what they call irresponsible lending and unfair interest rates.

Beyond Protests

Conversations about youth participation in the state of democracy across Africa are often reduced to a counting of first-time voters. Such discussions remain disconnected from the wide-ranging protests discussed above. The protests are usually successful. In Kenya, after six weeks of demonstrations and a promise to reverse the bill, President William Ruto fired his cabinet and pledged to cut wasteful spending.

However, there is limited evidence to suggest that youth-led movements have imagined new democratic frameworks beyond their participation in voting, protesting, and ensuring accountability. Youth-led organizations focused on government accountability have grown in number and influence over the years. They have leveraged technology to track government expenditures, established commitments to policy reform, and mobilized more youth participation. They have pushed back on the global financial system and its treatment of poorer countries. However, all these actions can appear to be simply tinkering on the edges of a continent that may be drifting into a new era led by popular authoritarians. To avoid this outcome, the youth movement must continue to play a more active role in governance instead of simply being facilitators of political transitions.

As we step into 2025, there is a palpable sense of anticipation for a brighter future across various facets of our lives, including the state of our democracies. The past year has been a mixed bag for African nations, with several countries undergoing elections that yielded new political dispensations including new administrations led by former opposition parties and in some instances governments of national unity. In some cases, the incumbent parties retained power. It was a year in which electoral democracy was tested (Mail & Guardian). The consensus around electoral democracy has been somewhat restored.

What then should we look out for in 2025?

The previous rounds of elections have demonstrated that changing leaders or political parties although necessary is not enough. Elections are a crucial component of democracy; they are not sufficient on their own to ensure transformative development. The reality is that many African electoral democracies have not delivered the expected outcomes, often resembling undemocratic regimes where elites prioritise personal gain over public service. We hold on to the statement that elections are a necessary but not sufficient condition for democracy. Perhaps the biggest disappointment for the electorate is to see those in new administrations behaving the same (if not worse) as the previous regime that they would have voted out. This happens across many countries on the continent.

What then is the missing part of the puzzle?

In our earlier writings, we have made a case for citizen-centred democracies. In this big bet, we build upon an ideal of citizen-centred democracy. One of the most pressing issues highlighted in recent discussions is the need for accountability in our democratic systems. The lack of accountability on the part of public officials has led to stagnation in Africa’s development agenda, and we must do more to hold our leaders accountable

It involves holding governments to a standard of performance and ensuring that they face consequences for bad governance, abuse of public resources and ineffectiveness. However, the current political landscape often complicates this process. Legislative bodies, which are supposed to oversee government actions, frequently operate under the same political party affiliations as the executive branch, creating a conflict of interest that undermines accountability. This has resulted in widespread allegations of corruption and abuse of power, further eroding public trust in government institutions. To address these challenges, there is an urgent need for citizens to expand their repertoire of public work beyond just casting their votes.

The concept of accountability is fundamental to a functioning democracy.

In 2025 we are making a bet on citizens to build upon their collective energy to come together in various associational and institutional platforms, demanding accountability from public officials at both national and local levels. If anything, the agitations amongst Gen Zs in Kenya, Senegal, Ghana and Nigeria provide hope for a citizen-driven redefining of democracy and good governance.

The big bet is that a consensus around accountability will significantly improve the quality of our democracies across Africa. In many instances, the assumptions have always been that Africa’s leaders will be moved by a certain moral compass towards duty, integrity and effective delivery of mandate. There is reason to believe that either the moral compass has been lost or sacrificed at the altar of personal accumulation.

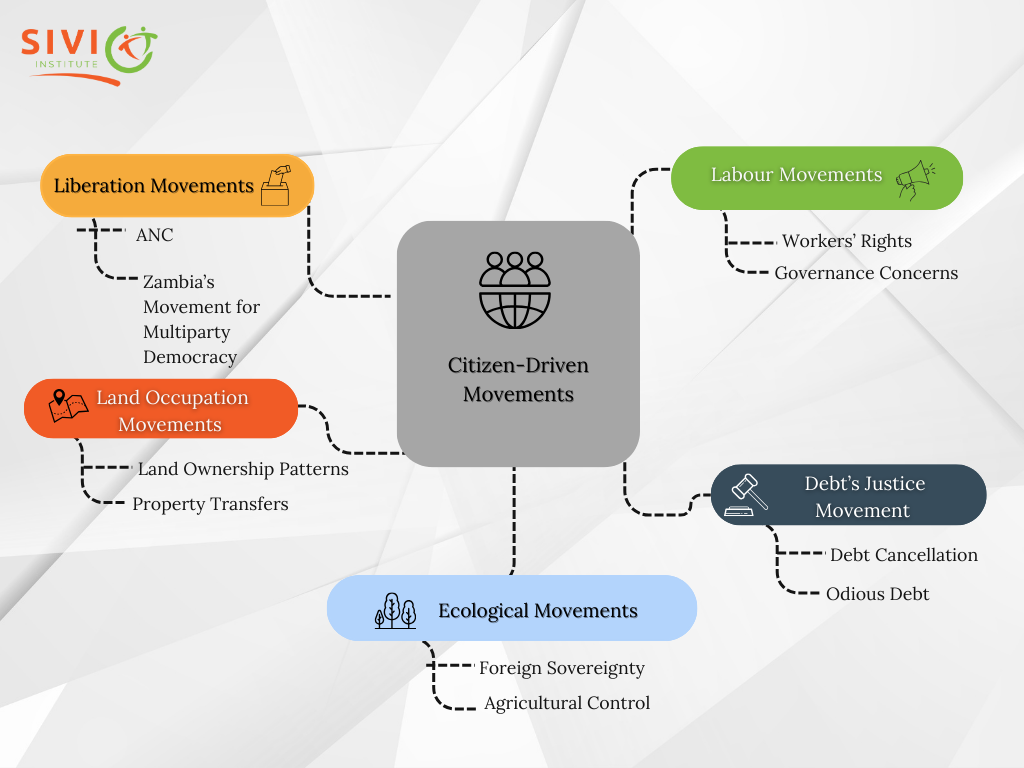

Figure: History of Citizen-Driven Movements of Accountability

Several civil society organisations have already begun to pave the way for accountability-focused initiatives. For instance, platforms like Corruption Watch and BudgIT Nigeria have worked tirelessly to expose corruption and track government performance. These efforts are crucial, but they must be expanded and integrated into broader social movements to create lasting change. Currently, many citizen-led initiatives emerge in response to crises, often achieving short-term gains but lacking the mechanisms for sustained impact. By collaborating with established civil society organisations, these movements can enhance their effectiveness and ensure that accountability remains a central theme in the political discourse. Moreover, tracking the conversion of electoral promises into actionable policies is essential. Political parties often present lengthy manifestos filled with promises during election campaigns, yet these commitments frequently go unfulfilled. Citizens must demand action from their leaders on promises and pledges and ensure that they translate into tangible actions that benefit the public.

As we look ahead, it is crucial to foster a culture of accountability that permeates all levels and sectors of governance, including health, education, and public finance. This requires a proactive approach, where citizens are not just passive observers but active participants in demanding transparency and good governance. The role of the media, civil society, and grassroots movements cannot be overstated in this endeavour. In conclusion, the journey towards a more accountable and effective democracy in Africa is a collective responsibility. As we enter 2025, let us commit to revitalising our democratic processes by holding our leaders accountable and ensuring that they deliver on their promises. By doing so, we can create a brighter future for all citizens, where democracy truly works as it should.

The time for action is now, and together, we can make a significant impact on the trajectory of our nations.